Can a chemical reaction measure the size of its container?

All modern society rests on a suite of basic chemical processes, developed over centuries, that let us feed ourselves, power our cities, and make virtually every artifact of technology we manufacture. We know chemical processes that let us fix nitrogen, string together polymers, coat surfaces with metal, and perform a thousand other wonders. This is a post about a chemical capability which we do not yet have. It’s not a particularly useful one, but we’ll find there are things to be learned by considering it nonetheless.

My favorite useless-but-cool chemical reaction is the Briggs-Rauscher oscillating clock reaction, a reaction common in chemistry classrooms which dramatically changes color from blue to clear every few seconds for a minute or more. “Chemical oscillator” reactions like this one are famous among chemists because an oscillating reaction seems so counterintuitive (when they were first discovered, nobody believed the discoverer!). Steady oscillation is a behavior you’d expect from a mechanical or electronic system but not from a purely chemical one. In the case of the Briggs-Rauscher reaction, this behavior’s powered by a sort of entropic battery and can be understood in loose analogy to electromechanical clocks: one reactant is steadily consumed to power an oscillating system of other chemicals, much like a grandfather clock is powered by the potential energy of a weight or an electronic oscillator is powered by a battery. This clever system demonstrates (at least to me) that, if we’re creative, the medium of chemistry affords sufficient freedom to make much more than one imagines at first look.

Let’s trust this is true – that pure chemical systems can do many things that you’d think you need electromechanics for – and let’s not worry about doing things that are useful, just things that are interesting. What might we hope to make? Could we make reactions that detect temperature? Reproduce music? Precipitate entire 3D objects? Do math? Are there chemical reactions which are Turing-complete? Is there a simple set of “chemical modules,” analogous to the logic gates or the simple machines, which one might use as basic building blocks for more complex processes?

This broad direction seems interesting, and I know of no theoretical work discussing it. We’ll revisit it at the end. For now, however, I’d like to explore one specific application which I find particularly intriguing. Let us ponder whether one could conceivably make…

A chemical reaction that measures the volume of its container

Is it possible for a purely chemical system to measure the volume of its vessel? This is easily done with the mechanical methods of a volumetric flask, a scale, or a ruler, but can we do it with pure chemistry?

I should clarify what exactly I mean by this. I want a reaction such that we can (a) combine some chemicals in a beaker (without too much sensitivity to initial conditions), (b) wait some time for a reaction to occur, and (c) measure the final concentration of one of the reaction products and straightforwardly read out the volume of solution (for example, maybe the solution is saltier or more opaque in proportion to its volume). Is such a system possible?

There is an easy solution which we’ll disallow: if you just dissolve a known mass $m$ of solute in the solution, the volume $V$ can be read off from the final concentration $m/V$. This violates our stipulation on sensitivity to initial conditions – we needed exactly mass $m$ – and, for clarity and good measure, let’s also disallow it with the natural requirement that, if you just combine the full contents of two beakers at time zero, you should read out the sum of their volumes at the end (a criterion this hacky solution does not satisfy).

Making such a volumetric reaction is trickier than it might seem at first glance. If you ponder it for some time, you’ll find that the difficulty is that volume is an extensive quantity (one that increases proportional to the amount of stuff, like a system’s mass), but chemical reactions are local and only depend on intensive quantities like concentrations or temperature (which are independent of the total size of the system). How can we design a local system that takes a global measurement?

The reaction-diffusion equations

Now is the point when I confess I know little about practical chemistry and have no idea how to either design or test a chemical reaction. That said, I am a theorist, and I know some nice equations that can help out. Our proposition is sufficiently interesting that it’s worth figuring out if it’s even possible in principle, and for answering that question, we can use the reaction-diffusion equations, a mathematical model for a reacting chemical system spread across a volume.

The reaction-diffusion equations describe the time-evolution of a concentration vector $\mathbf{u}(x, t) \in \mathbf{R}^n$, where $x$ is a spatial coordinate, $t$ is time, and the $n$ elements of $\mathbf{u}$ represent the concentrations of $n$ chemical species. The concentration vector evolves according to

\[\begin{equation} \label{eqn:rd} \partial_t \mathbf{u} = \mathbf{D} \nabla^2 \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{r}(\mathbf{u}), \end{equation}\]where $\mathbf{D} = \text{diag}(D_1, …, D_n)$ is a diagonal matrix of diffusion coefficients, $\nabla^2$ is the Laplacian, and $\mathbf{r}(\cdot)$ is an arbitrary local reaction function. The first term in this evolution describes each species undergoing ordinary diffusion, which acts to spatially smooth out their concentrations, while the second term describes a local reaction in which chemical species multiply or change identities. Let’s suppose we’re working in 1D with a total volume $V$ and periodic boundary conditions. The question we pose to ourselves is: can we find diffusion constants $D_i$ and a reaction function $\mathbf{r}$ such that, as $t \rightarrow \infty$, one of the concentrations - say, $u_n$ - is proportional to V?

Turing patterns

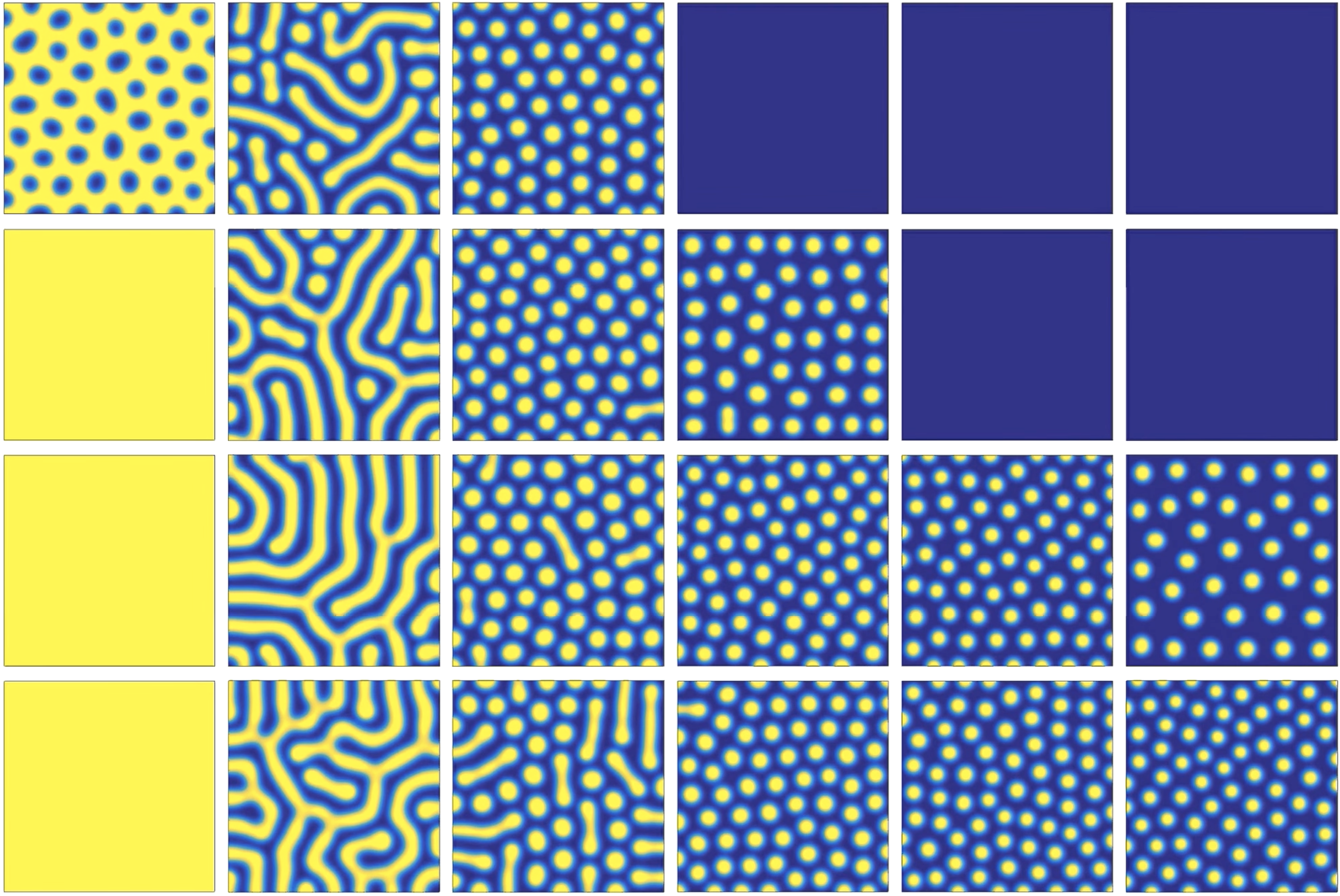

If you’ve heard of reaction-diffusion equations before, it’s probably in conjunction with Turing patterns. Turing patterns are beautiful, amorphous-looking spatial patterns in the concentration of chemical species that emerge spontaneously as a result of reaction diffusion evolution with certain kinds of reaction term. Here are some examples (source here):

(Note that these are 2D, while we’ll be working in 1D.) Here’s a site with animations showing how these patterns develop spontaneously in time. If Turing patterns look somewhat biological to you, that’s a good instinct - lots of coloration patterns on animals are created by similar processes.

The fact that Turing patterns give spatial structure from nothing seems like a good start in our endeavor to make a volumetric reaction. The bumps have a characteristic spacing, so it seems like all we have to do is let the pattern form and count the ridges. We’ll then just have to make sure some other chemical species’ concentration encodes the final count.

While that sounds great, it’s not obvious (at least to me) how to then make a reaction that counts the ridges, so we’ll need to think harder. My first thought was to instantiate a big set of Turing patterns in different components of $\mathbf{u}$, each with a different characteristic wavelength, and see what the longest-wavelength species that grew a bump was, but then I had a better idea.

The plan

Our core difficulty is that it’s difficult to escape the world of intrinsic quantities. Measuring volume would be easy if we had one extrinsic quantity to use as a foothold. Here’s an idea to this effect: create exactly one “concentration bump” of a known shape at a random location. The “bump density” $1/V$ (in units of bumps per volume) is easy to measure chemically, and it’s easy to convert from that to $V$!

Stable bumps of known shape are easy to make using reaction-diffusion systems, as Turing patterns make evident. Turing patterns have fixed bump density, though – not fixed bump count, which is what we need – so we’ll have to adapt the system so one bump suppresses all others.

The execution

I figured out how to do this with a reaction-diffusion equation with six chemical species. These consist of four “fast-diffusing” species, for which the time to diffuse across the vessel $V^2 / D_i$ is much shorter than all other timescales and concentration is uniform, and two “slow-difffusing” species which create spatial structure. These species play the following roles:

- $u_1$ (fast): a timer whose concentration steadly grows from zero and regulates other reactions.

- $u_2$ (slow): a randomly-diffusing agent which amplifies random variation in its initial concentration to create a random concentration profile.

- $u_3$ (fast): a maxfinder whose concentration converges to just below the max concentration of agent $2$, with only the peak above it.

- $u_4$ (slow): a bump-forming agent which forms a bump of a certain size starting from the site of max concentration of agent $2$ at a prescribed time.

- $u_5$ (fast): a bump measurer which is produced by the indicator bump and converges to concentration inversely-proportional to $V$.

- $u_6$ (fast): a readout agent which concerges to concentration $\propto 1 / u_5$.

I’ll defer further discussion and the equations themselves to the Appendix. Let’s just jump to the good part: here are videos of the reaction working.

Fig 1. Simulations of the volumetric reaction for $V = 3,5$. A timer component regulates a multi-step process in which one bump of known size forms, emits a measurement agent, and allows the deduction of the system size.

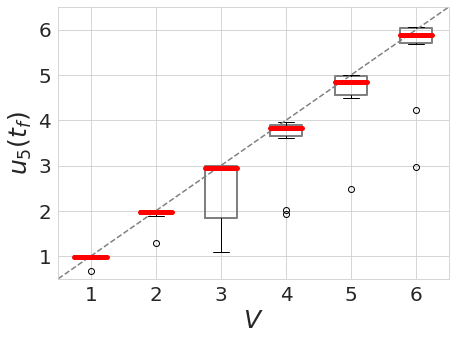

Note how, in both cases, the concentration $u_6$ of the readout species is equal to to the volume of the system ($V=3,5$, respectively) at around $t=60$! Figure 1 shows the spread of final concentrations for $V \in {1,…,6}$. The medians land right on the true volumes. (The long tails of outliers reporting smaller volumes reflects cases in which more than one bump was formed; the reaction’s pretty noisy, but I count this as success since it works most of the time.)

Fig 2. Final readout concentrations $u_5(t_f)$ with $t_f = 70$ over 10 trials with $V \in \{1,...,6\}$.

Discussion

We’ve seen that it’s possible for a reaction-diffusion equation with random initial conditions to measure the global volume of its vessel despite its being a fundamentally local process. So, could there be real chemical species that’d make this work in reality? Perhaps the greatest stretch is the continuously-increasing timer ($u_1$) that regulates other reactions, but then we’ve already seen that clock reactions exist in practice, and in the worst case we could drop the timer and have the experimenter mix in new chemicals at specified times. The readout $u_6$ converging to $\propto 1 / u_5$ is a bit suspicious, too – it’s rare for a reaction to be sensitive to the inverse of a concentration – but I suspect one could design a process that approximates that sensitivity in some regime, and in the worst case again, the chemist could just measure $u_4$ and make that calculation manually. It’s worth noting that this process in reality would probably include additional species for support (just as a motor contains many more parts than those which are directly part of the core process). That said, I see nothing that suggests that something like it couldn’t work in the real world. If you know more chemistry than I and have thoughts, please reach out!

So what? This reaction is cool, but it’s not useful; its value is in its serving as a test case for a broader idea. Having crafted a volumetric reaction-diffusion system, we could now use it as a module in other more complex systems, like one that renders an image or pattern autoscaled to the space available. We’ve crafted a transferrable module which robustly does something interpretable and which we can combine with other modules to make more complex systems. This process of crafting modular abstractions is how all fields of engineering work (think of physical mechanisms, simple circuits, software packages, etc.). Chemical engineering has basic reactions for doing simple manipulations to chemicals (cutting, splicing, oxidizing, polymerizing, etc.) The things one can ultimately make are defined by the elements of this basic modular algebra, and so it’s fascinating to think that there could be a “different basis” of chemical modules which do things like measure, render, count, perform logic, etc.

There are various senses in which an algebra of basic chemical processes could be “complete.” One might be: can reaction-diffusion processes be used to simulate any isotropic PDE? Most PDEs are not reaction-diffusion processes – for example, one might contain terms like $u_1 \nabla^2 u_2$ – but perhaps a reaction-diffusion process with some auxiliary fields could simulate such terms (much like auxiliary particle fields create effective interaction terms in particle physics). More generally, we could ask if one could make an arbitrary Turing machine. The hard part seems to be breaking the left-right symmetry, but I’m fairly confident it’s doable. It’d be rather beautiful if Turing patterns were Turing-complete.

There is a game that could be played here which is akin to code golf: how few chemical species can we make this reaction with? In my case, I used six, and had I cleverly reused some of them, I expect I could get it down to three or four. I could see this game being fun given an interesting set of objectives. Since all engineering fields use this paradigm, we could in principle play it in lots of other domains, too, trying to e.g. make a circuit that does a certain task with as few components (or as few logic gates) as possible or designing a physical mechanism with as few degrees of freedom as possible.

My main field of study isn’t chemistry, it’s deep learning theory, and there are lessons I take from this exercise as to how we might think about neural nets. Deep learning has a reputation for being modular – the basic architectural units in PyTorch are literally called Modules – but it’s unique in that nobody knows how to think about what the modules are really doing. Modern chemical engineering is composed of well-understood steps, but medieval alchemy, by contrast, was composed of lots of poorly-understood steps. Deep learning in 2022 is much more like alchemy: we have modules like transformer layers, batchnorm layers, and so on, but we don’t truly understand what they do or how we ought to combine them to accomplish a broader task. I imagine thinking in terms of the actions of modules could’ve helped the alchemists clarify their thinking and develop chemistry, and I similarly expect thinking in terms of what quantitative effect each deep learning module does will prove clarifying for the field. It’s my belief that, in doing so, we’ll eventually arrive at a state in which the design of a deep learning system resembles the selection and combination of well-defined modules like in every other field of engineering.

Appendix: details of the reaction

The reaction-diffusion system of Equation $\ref{eqn:rd}$ is defined by its diffusion constants and reaction function. We choose the diffusion constants to be

\[D_1 = D_3 = D_5 = D_6 = \infty, \ \ D_2 = 2, \ \ D_4 = 1,\]where $D_i = \infty$ means that species $i$ diffuses much faster than all other timescales (implemented in simulation via global averaging every timestep). We choose the six componts of the reaction function $\mathbf{r}(u)$ to be

- $r_1 = .1,$

- $r_2 = .1 \, u_1 \ I(0,t_a),$

- $r_3 = 10^3 \ \text{max}(u_2 - u_1, 0),$

- $r_4 = 30 \, (1 - u_4) \ \mathbb{1}_{u_2 > u_3} \ I(t_a - .1, t_a) + .15 \ I(t_a, t_b) + (2 u_4 - 1) - (2 u_4 - 1)^3,$

- $r_5 = (10 u_4 - u_5) \ I(t_b, \infty),$

- $r_6 = (2.9 u_4^{-1} - u_5) \ I(t_b + .5, \infty),$

where $t_a = 2$, $t_b = 5$, and $I(t_1, t_2) \equiv 1_{t_1 \le u_1 < t_2}$. All components are initialized as random functions with variance $.2$ (see the code for details). I arrived at these formulae after a lot of trials and error, working from the top of the list down, developing each step of the mechanism sequentially. The hardest part was reliably getting a single bump to develop in $u_4$; I was close to thinking this might be impossible to get one bump to spontaneously form and suppress all others, but using the initial randomness to break the symmetry let me do it.

Here’s the colab notebook I used to implement these. Slightly different calibrated reaction constants were used to generate Figure 2.