A complete characterization of the expressivity of shallow, bias-free ReLU networks

In the theoretical study of neural networks, one of the simplest questions one can ask is that of expressivity. A neural network $f_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\cdot)$ can represent (or “express”) many different functions, and which function is expressed is determined by the choice of the parameters $\boldsymbol{\theta}$. The study of expressivity simply asks: which class of functions may be represented?

Among the pantheon of ML algorithms, neural networks are famous for their high expressivity. This fact is requisite to their power and versatility: practitioners find that a big enough neural network can represent functions complicated enough generate language and images.1 You may have heard of the classic universal approximation theorem which roughly states that an infinitely-wide neural network can represent any function at all.

The fact that nets’ expressivity is so high means that the notion of expressivity alone is usually unhelpful: it’s good to know that your network can represent virtually all functions, but this information is vacuous if you want to know which function it’ll actually learn! The one place where I’ve found the notion frequently useful is in negative cases: if a neural network architecture can’t express some class of function, it cannot learn it — no need for further questions.

This blogpost is about one of those cases. The most common activation function used today is $\mathrm{ReLU}$, and so one would be forgiven for thinking that any big enough $\mathrm{ReLU}$ network will be able to express any function. It turns out this reasonable intuition is wrong: there are lots of functions that a shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ network with no biases can’t represent, even if it has infinite width. To spoil the answer, such a net can trivially only represent homogeneous functions (i.e., those such that $f(\alpha x) = \alpha \cdot f(x)$ for $\alpha > 0$), but less trivially, it also can’t represent odd polynomials of order greater than one. This fact’s independently showed up in my research no fewer than three times in the last month, which I take as a pretty strong sign that it’s worth articulating and sharing.

The structure of this blogpost will be as follows. I’ll begin with a refresher on the universal approximation theorem. We’ll then state a theorem about the expressivity of shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ networks and list some cases where it applies. We’ll conclude with some experiments showing $\mathrm{ReLU}$ networks failing to learn simple cubic and quintic monomials.2

Review: the universal approximation theorem

The UAT states that a shallow neural network with biases and a nonpolynomial nonlinearity can, given sufficiently large width, approximate any function to within any desired error. More precisely, suppose we have $d$-dimensional data $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d$ sampled from a distribution $p(\mathbf{x})$ and a feedforward function of the form

\[f_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf x) = \sum_{i=1}^n a_i \cdot \sigma( \mathbf{b}_i^\top \mathbf{x} + c_i),\]where $a_i \in \mathbb{R},\ \mathbf{b}_i \in \mathbb{R}^d,\ c_i \in \mathbb{R}$ are free parameters, and we write $\boldsymbol{\theta} \equiv {(a_i,\, \mathbf{b}_i,\, c_i)}_{i=1}^n$ to denote the tuple of all free parameters. Suppose we wish to approximate some desired function $f_* : \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ such that the error…

\[\mathcal{E}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} := \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x} \sim p} \left[ (f_*(\mathbf{x}) - f_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x}))^2 \right]\]is less than some threshold $\epsilon$. So long as $n$ is sufficiently large and the functions $\sigma, f_*, p$ satisfy some natural regularity conditions (see the Wikipedia page), we can always find a way to choose $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ so that $\mathcal{E}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} < \epsilon$.

The limitations of shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ networks

The nonlinearity $\sigma(z) = \mathrm{ReLU}(z) := \max(z,0)$ is nonpolynomial, so the universal approximation theorem indeed applies to shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ networks. All guarantees are off, however, if we remove the biases (i.e. set $c_i = 0$). A $\mathrm{ReLU}$ network without biases has clear expressivity limitations: for example, it can only express homogeneous functions $f(\alpha \mathbf{x}) = \alpha f(\mathbf{x})$. (For this reason, when studying shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ nets, it is common to consider only functions on the sphere.) The point of this blogpost is to show that there’s an additional limitation which is often overlooked.

We start with an observation about the functional form of a shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ net.

Click for proof

Any function that doesn’t have this linear-plus-even form can’t be represented by a shallow ReLU net without biases. The following definition and proposition show that if a function has this form, it can be represented (or more precisely, approximated to arbitrary accuracy) by a shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ net.

Definition 1: Let $f_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x})$ be a shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ network with no biases and width $n$. We will say a function $f_\ast$ is shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ approximable if, for every probability distribution $p(\cdot)$ with compact support and every $\epsilon > 0$, we may choose $n$, $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ such that $\mathcal{E}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} < \epsilon$.

Click for proof sketch

We can prove this by first using homogeneity to only have to consider functions on the sphere, then using Fourier analysis with spherical harmonics to show that the $\mathbf{ReLU}$ basis function is enough to represent all linear and even-order polynomials. Any continuous function on the sphere may be approximated by a polynomial by the Stone-Weierstrass theorem (I think I’m using that right). I’m not going to flesh out the details here, but ChatGPT can probably do it if you’re curious.

Out of this we get a nice corollary that gives us a property to look for that tells us that no component of our function is representable:

Corollary 1: Suppose $p(\mathbf{x}) = p(-\mathbf{x})$ and $f_\ast(\mathbf{x})$ is an odd function satisfying $\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}[f_\ast(\mathbf{x}) \cdot \boldsymbol{\beta}^\top \mathbf{x}] = 0$ for all $\boldsymbol{\beta}$ (i.e., it’s orthogonal to all linear functions). Then $\mathbb{E}_{x \sim p}[f_\ast(\mathbf{x}) f_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{x})] = 0$ for all ${\boldsymbol{\theta}}$, and when choosing $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ to minimize the MSE $\mathcal{E}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}$, the best the network can do is to represent the zero function.

(We can actually prove this corollary without going through the above machinery, just integrating directly against the measure and using properties of the $\mathrm{ReLU}$ function, but it’s illuminating to go through the above propositions because we get a complete picture of the representable functions.)

Some examples

So what? Does this ever actually show up? Here are two cases where it’s shown up in my recent research. Notice how you could easily think shallow $\mathrm{ReLU}$ networks could do the job if you didn’t know better.

Sinusoids on the unit circle. If $\mathbf{x}$ is sampled from the unit circle, either uniformly over all angles or uniformly over evenly-spaced discrete points, then the network can’t achieve nonzero learning on functions like $\sin(k x_1)$ with $k = 3, 5, 7, \ldots$

Cubic monomials and higher-order friends. Suppose the coordinates of $\mathbf{x}$ are sampled independently (but not necessarily identically) from mearn-zero (say, Gaussian) distributions. The network can’t achieve nonzero learning on any monomial $x_i x_j x_k$ with nonrepeated indices. The same is true of monomials of order $5, 7,$ etc.

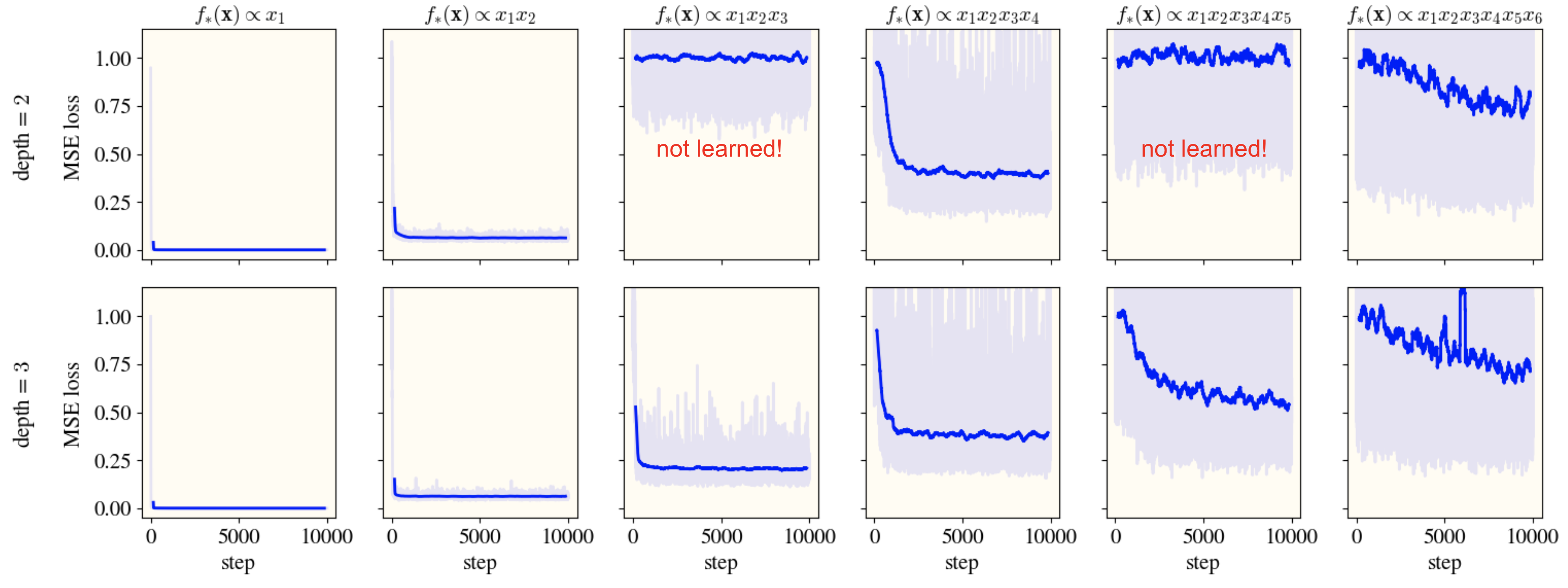

This last one’s pretty surprising to me! To test it, I trained bias-free $\mathrm{ReLU}$ nets, both shallow (i.e. depth 2) and deep (depth 3), on monomial functions of Gaussian distributions. As you can see, the deep net can make progress on monomials of every order, but the shallow net can make no progress on odd monomials of order $\ge 3$. Weird!

Concluding thoughts

This doesn’t matter at all for deep learning practitioners, but it’s useful to keep in mind for deep learning theorists. It’s useful to study the simplest model that can perform a learning task, and it’s good to know that the first thing you might try — a shallow, bias-free $\mathrm{ReLU}$ net — can’t even learn every function on the sphere.

Thanks to Joey Turnbull, who first brought the experiment reported above to my attention.

-

Of course, the more remarkable fact is that neural networks not only can represent these functions but also do learn them when trained. This is beyond the power of expressivity to explain. ↩

-

As a disclaimer, I’ll say that I’m confident that none of the content in this blogpost is new: I’m sure many researchers over the years have realized all of this. I’m not sure where to find these results in the literature, and it’s easier for me to write this then to find a good reference, so I’m just going to develop it all from first principles, but if you know a reference, do send it my way. ↩