Experiments in self-assembly

In 2018, I designed and prototyped a series of self-assembling objects. I never published anything about it then, so I’m doing it now. I’ll give background and my motivation, show some cute demos, and conclude with some reflections.

Background

I’ve always liked cute interactive technical projects. This was particularly true in college, during which I made lots of mostly-useless-but-fun things, including

- a laser-activated light switch

- a robotic articulated necktie which could grab food and bring it to the wearer’s mouth

- various 3D printed ball mazes

- lots of balancing sculptures

- and a campus-wide puzzlehunt.

I thought self-assembling systems and other passive mechanics were particularly cool — some demos that inspired me included this self-assembling “chair,” this swarm of cubic robots, and this robot origami, all from MIT. As a senior, I got a small grant from the 3D printing service Shapeways to explore 3D printed self-assembling systems.

I spent a semester on the project and came up with some cool prototypes. None of them are particularly scalable or practical, but they are cute.

Self-assembling circuit

I designed a self-assembling circuit. It consists of four pieces, each of which has two magnetic surfaces to link up to its two neighbors. The four pieces are hollow and contain circuit components: a battery, a resistor, an LED, and a blank wire, respectively. When all four pieces are joined in a loop, the LED lights up. As far as I know, this is the first self-assembling circuit ever made (as long as you don’t count naturally-occurring circuits in biochemistry!).

The four pieces will link up after being shaken together for a minute or two. Here’s a demo video:

Some technical facts:

- The magnetic pattern on each connecting surface is addressed uniquely to its counterpart. These pieces will always assemble the same way.

- The internal wires are soldered to the little magnets on the connecting surfaces. This was harder than it sounds because a soldering iron will heat up a magnet enough to demagnetize it! I ended up attaching each demagnetized magnet to a working magnet to get around this.

“Magnacubes”

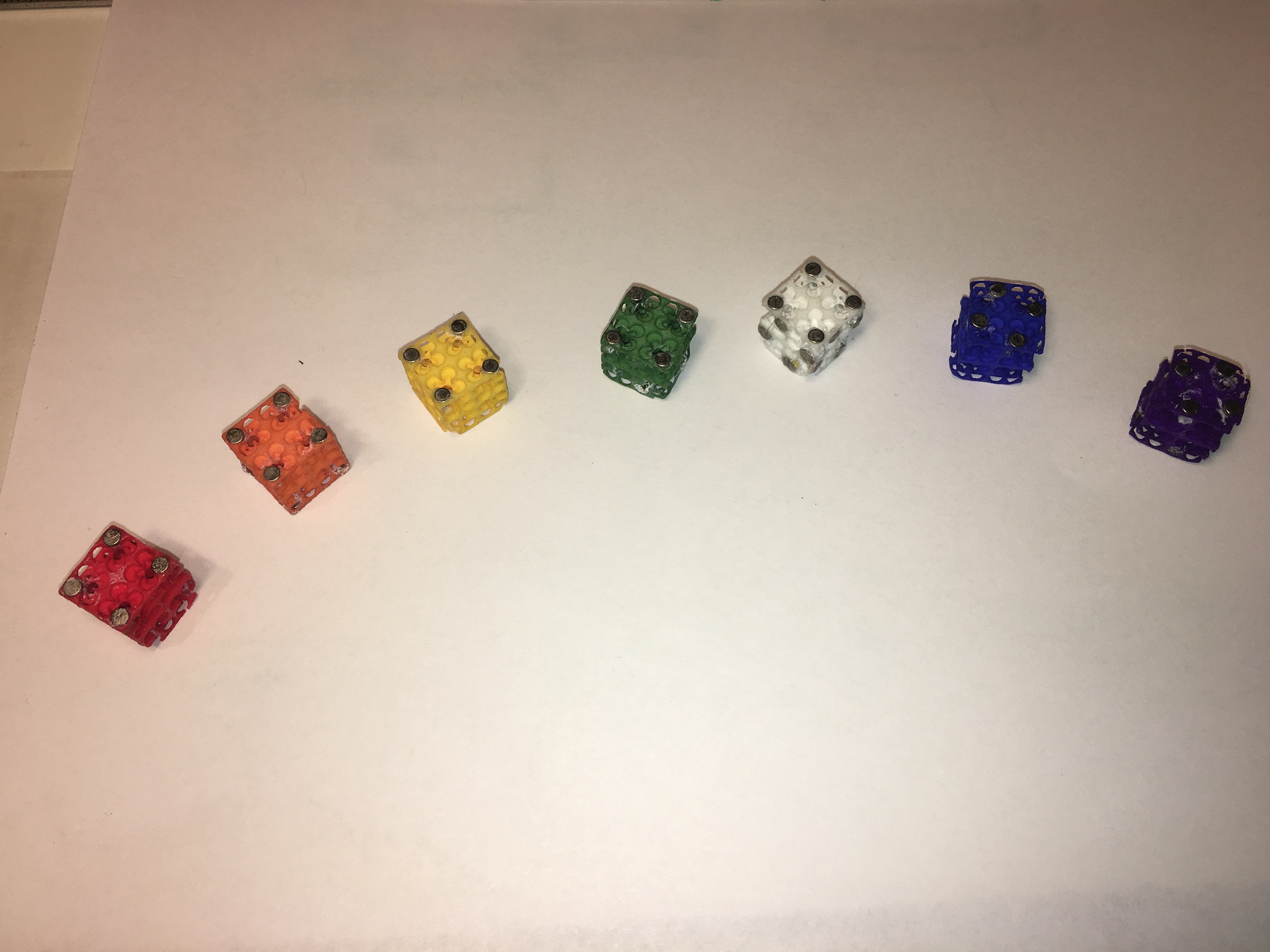

Before the self-assembling circuit, I tried the same concept with ordinary cubic blocks. Here are two pictures (before and after assembly, respectively) and a video.

“Instacube”

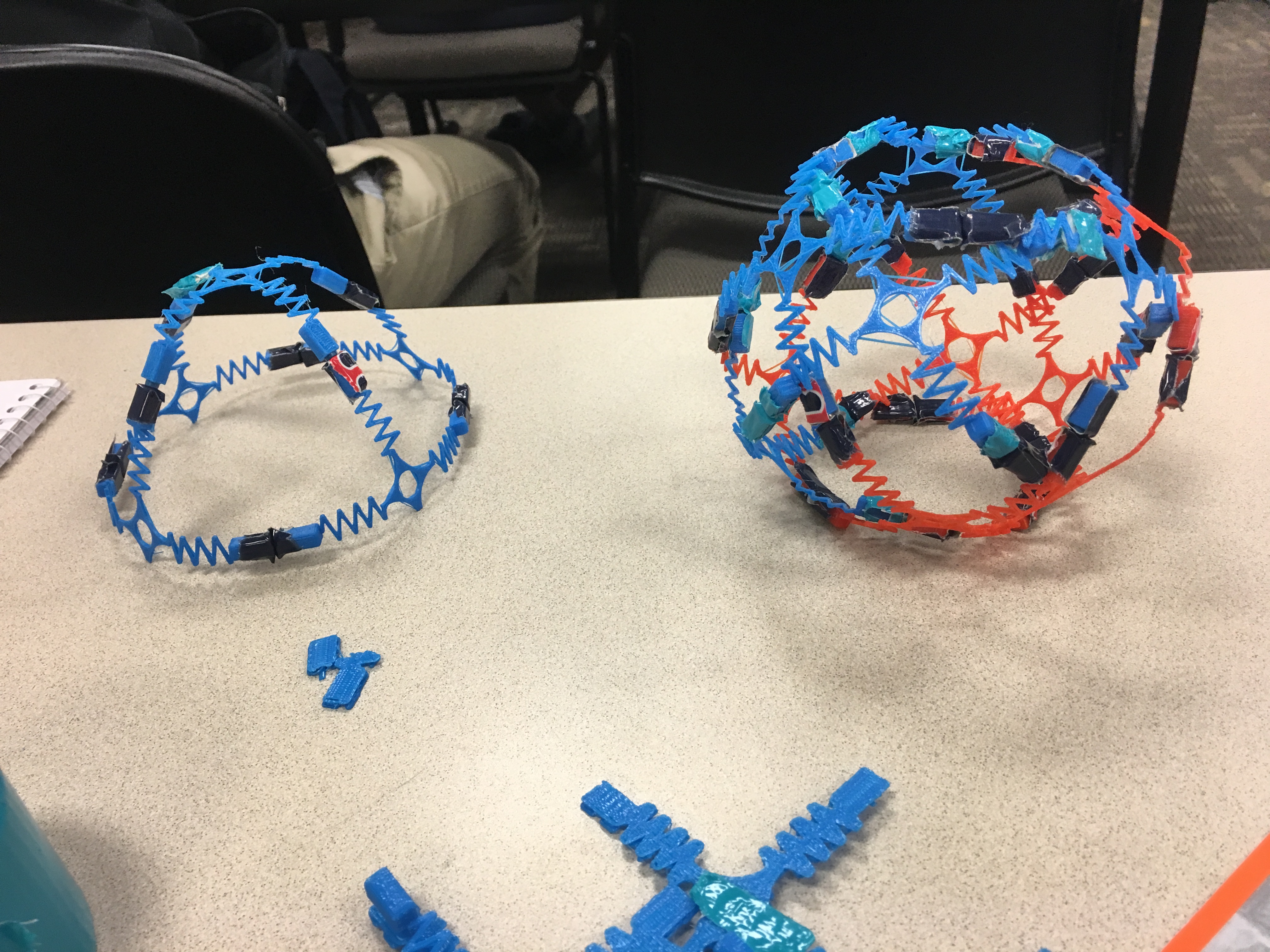

These linked rods take on a cubic shape under the influence of gravity.

“Self-healing” magnetic material

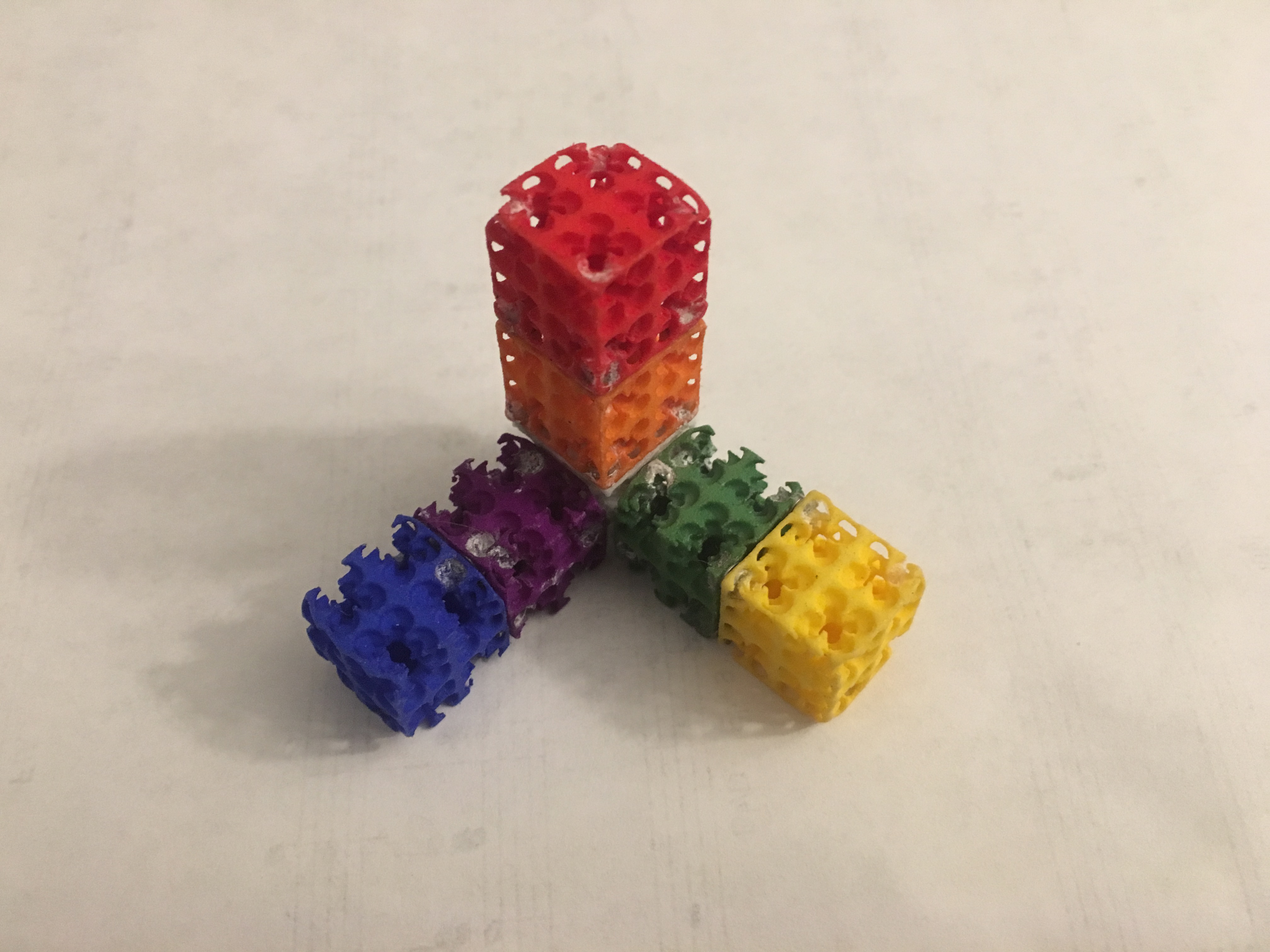

I designed a repeating unit with four embedded magnets on springs pointing out in cardinal directions.1 These units can be linked up in big sheets or closed 3D structures. Individual magnetic bonds will reform if they’re broken, so you can pass a thin object through the material without any lasting damage. Here are a picture of some assembled units and a video showing the “self-healing” property.

Other ideas and failures

I spent a lot of time exploring “self-assembly by pulled string” in which you could pull a string taut and a 3D object would pop up. This was motivated by a desire for an instantly-assemblable tent. I got some promising initial results, but ultimately it was too hard to get the tension to transmit through the whole chain with the materials and geometry I was using. I’m sure something like this could work well enough to make a cool demo.

I also tried making something that’d assemble with buoyant forces when submerged in water, but didn’t get far. I’m sure that could be made to work in some capacity, too.

Reflections

It’s been six years since this series of projects. In that span, I’ve matured into a proper scientist. Looking back, they’re clearly immature work, but I still find most of these demos cool. I appreciate my past self’s ingenuity and initiative.

Given the opportunity, I’d offer my college self the following advice on this project:

- Find mentorship. Try hard to work with a professor. You’ll learn much more that way, and the small sacrifice of freedom is worth it.

- Choose projects that will teach you skills you want to learn, not projects that’ll lead to the cutest demos.

- Document finished projects better. You’ll want nice videos when you write a blog post in six years.

Most significantly, I am no longer enamored with flashy demos of the type that inspired me in college. They have undeniable aesthetic appeal, and they can certainly be technically impressive, but it’s not clear that they’re leading anywhere research-wise. In that respect, they seem more like art than engineering research. I still appreciate flashy demos as art, but I’m now quite wary when they’re presented as technical progress towards some important problem.

These days, I generally want technical research to feel like it’s going to be useful in the future — that it’s providing a useful tool, or that it’s revealing some piece of a larger puzzle, or that it suggests some new path forwards. I tend to feel that research is building an enormous tree of human knowledge, and that the best new pieces have lots of open joints to connect to yet more pieces that we could imagine discovering! One of my main reflections on my college research is that, when you’re brutally honest about it, it’s unclear that it’s actually leading anywhere!

I did not have this desire for utility at the start of graduate school: at that time, novelty and aesthetic appeal were probably my primary considerations, and I frankly resented the notion of doing something more like what everyone else was doing in order to have more of an impact. I suppose I ultimately landed somewhere in the middle: ML theory has proven important enough to do impactful stuff, but also wide open enough to do creative and beautiful work.

-

The north-facing and south-facing magnets are “south-pole-outwards,” and the east-facing and west-facing magnets are “north-pole-outwards.” This choice is nice for making big sheets from many units. ↩