Could you propel a spacecraft using sports projectiles?

In the fall of 2020, Ryan Roberts and I gave a remote talk for high schoolers through Berkeley Splash, our third exploring real physics through absurd scenarios instead of technical math. His talk discussed methods and consequences of making the Moon as big as the Earth, while mine aimed to find the best way to propel a spacecraft using only sports equipment. This is a writeup of the answer.

Since the dawn of civilization, humans have gathered for sports competitions, with rounds of faceoffs ultimately whittling the athletes down to a sole champion. This time-honored tradition has flowered throughout history; the modern Olympic Games involve dozens of sports split into hundreds of events. This explosion of athletic diversity has made determining an ultimate champion a lot more complicated, though; wouldn’t it be nice if there were some way we could determine who, of all the gold medalists, is actually the best? What if there were some grand final competition among the event champions to determine an ultimate victor?

For the consideration of the International Olympic Committee, I hereby propose the event of Rocketball as the Games’ final event. The rules are simple. To start, every gold medalist will be launched into Earth orbit with nothing but their wits, a spacesuit, and an absurd amount of equipment from their sport. They have no traditional rockets; to change course, the athletes have to hit, throw, fire, bowl, or otherwise propel sports equipment the other way, powered solely by their bodies. Instead of a goal line, there’s a target speed: whoever can accelerate themselves to reach that final speed first wins the Olympics1.

This proposal has one2 minor logistical problem: some sports are better than others. For example, it’d be way easier to accelerate by hitting tennis balls than by hitting ping-pong balls; a hit tennis ball is both heavier and faster, so (as we’ll see) as a rocket propellant it’s strictly better. Actually, in some cases, which sport is best can even depend on how fast the target speed is! To understand this, figure out how matches would play out, and see if we can come up with a fix, first we need to understand a little about how rockets work.

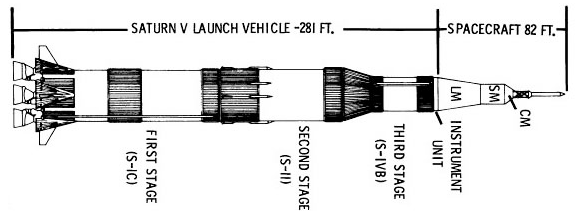

At their core, all rockets operate on the same principle: they fling matter in one direction, and the recoil force pushes the rocket in the opposite direction. This recoil force is the same sort of pushback you’d feel when firing a gun, holding a fire hose, or doing a fast chest pass in basketball, but in a typical rocket the matter being launched is exhaust from burning fuel moving several kilometers per second. True to this principle, rockets have two main parts: the fuel, which is gradually fired to propel the rocket, and the payload, which is the important other bits that the fuel’s there to accelerate. The fuel section also usually includes engines that help burn the fuel but fall off when they’re no longer needed. Here’s a diagram of the Saturn V rocket split into the launch vehicle (fuel + engines) and spacecraft (payload).

Our sportsball rockets will work basically the same way, but instead of liquid fuel they carry sports equipment, and instead of the most powerful engines ever built, they’ll be powered by lone humans flinging objects into the vacuum of space.

If you’re not familiar with rocketry or are very used to cars, you might wonder why the Saturn V has so much fuel for such a small payload. At some level, the reason’s that we want the payload to reach a very high speed (over 10 km/s), so we need a lot of fuel, but there’s another reason specific to rockets: the earlier fuel has to accelerate all the later fuel, so you need more of it. If a competitor gradually hit away a million golf balls, the first ball would give a very small bump in speed because it has to push the other 999999 balls, while the last one would give a relatively big bump in speed because it’s only accelerating the athlete. A rocket’s acceleration is inversely proportional to its current mass. Because of this, it turns out that the amount of fuel you need is an exponential function of the final speed, and ending up slightly faster can potentially take many times more fuel.

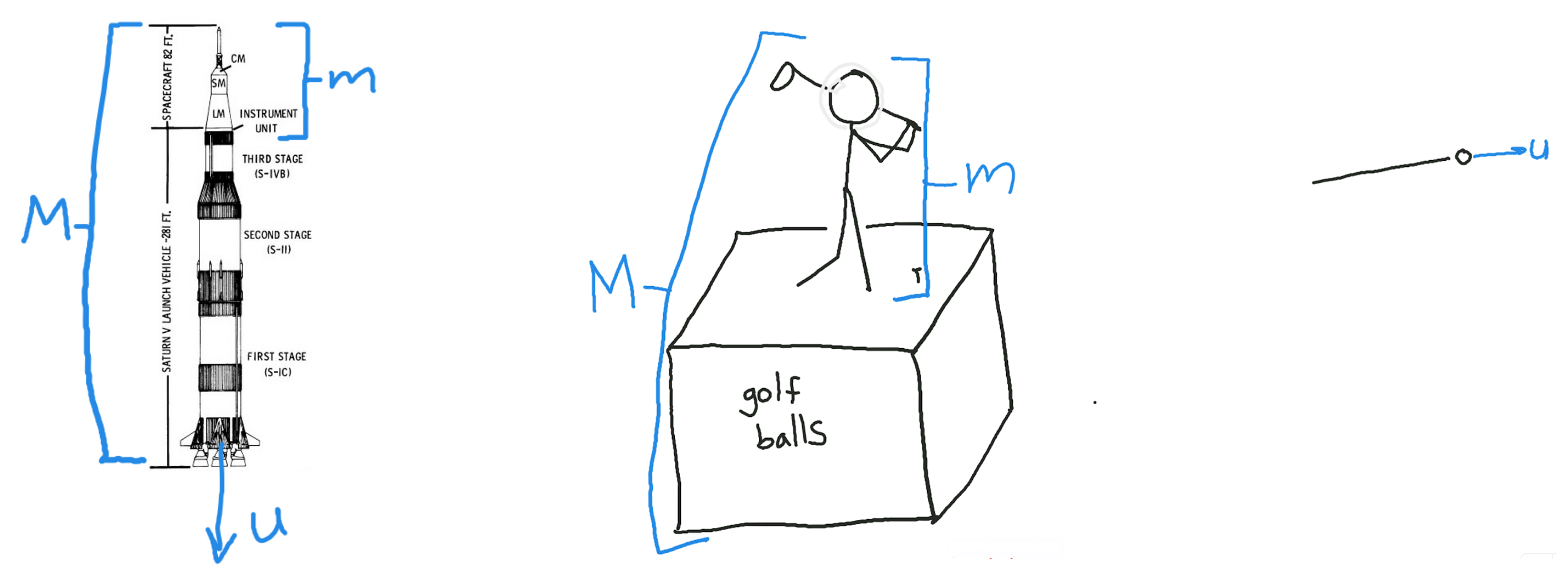

Rockets are complicated, but for a rocket accelerating in a straight line, it turns out we can find its speed over time if we know just a few numbers. These are the payload mass (which we’ll call \(m\)), the starting mass of the fuel and payload together (\(M\)), the relative speed the propellant’s fired at (\(u\)), and the thrust of the rocket (this is the average kickback force the rocket feels; we’ll call it \(F\)). Here’s a diagram illustrating what some of these are.

If you do the rocket science, you find that to reach a final speed \(v\), the rocket needs a starting mass of \(M = m e^{v/u}\), and it runs out of fuel and reaches speed \(v\) at a time \(t = \frac{(M-m)u}{F}\). For a given target speed \(v\), this choice of \(M\) is optimal - with less fuel, it won’t reach the target speed, but with any more, it’ll reach it slower.

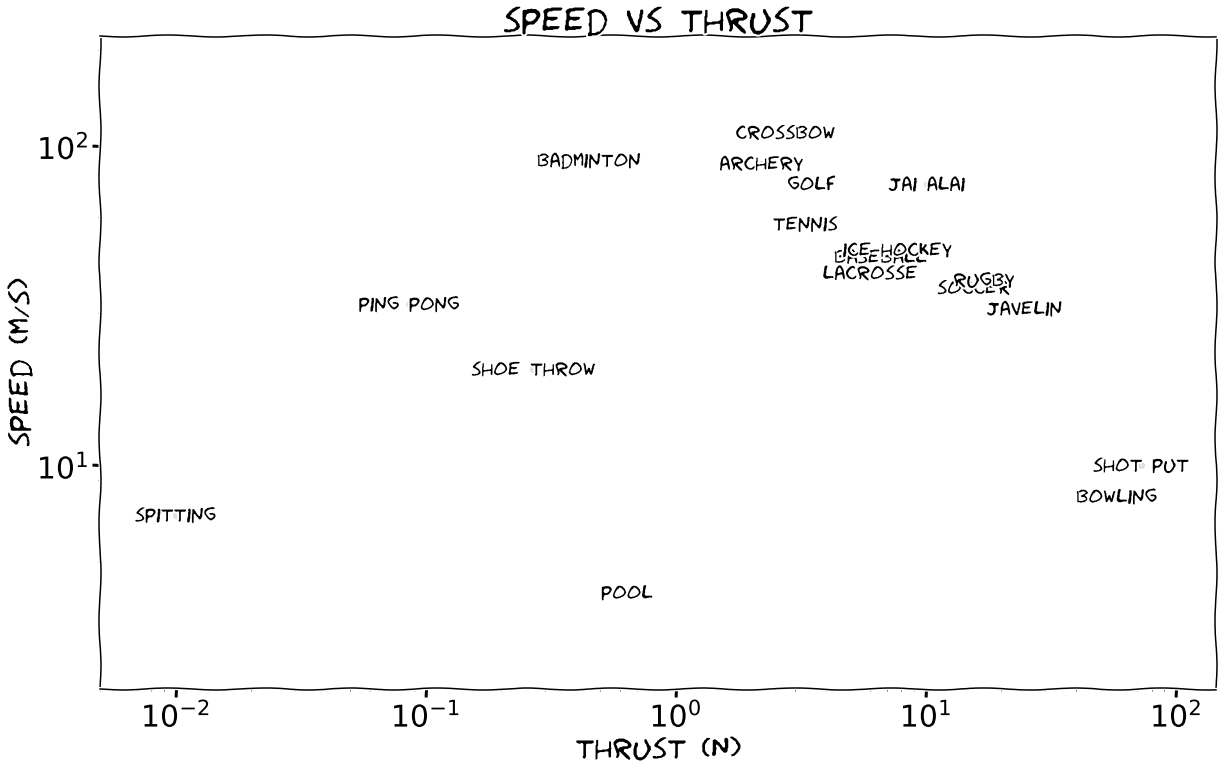

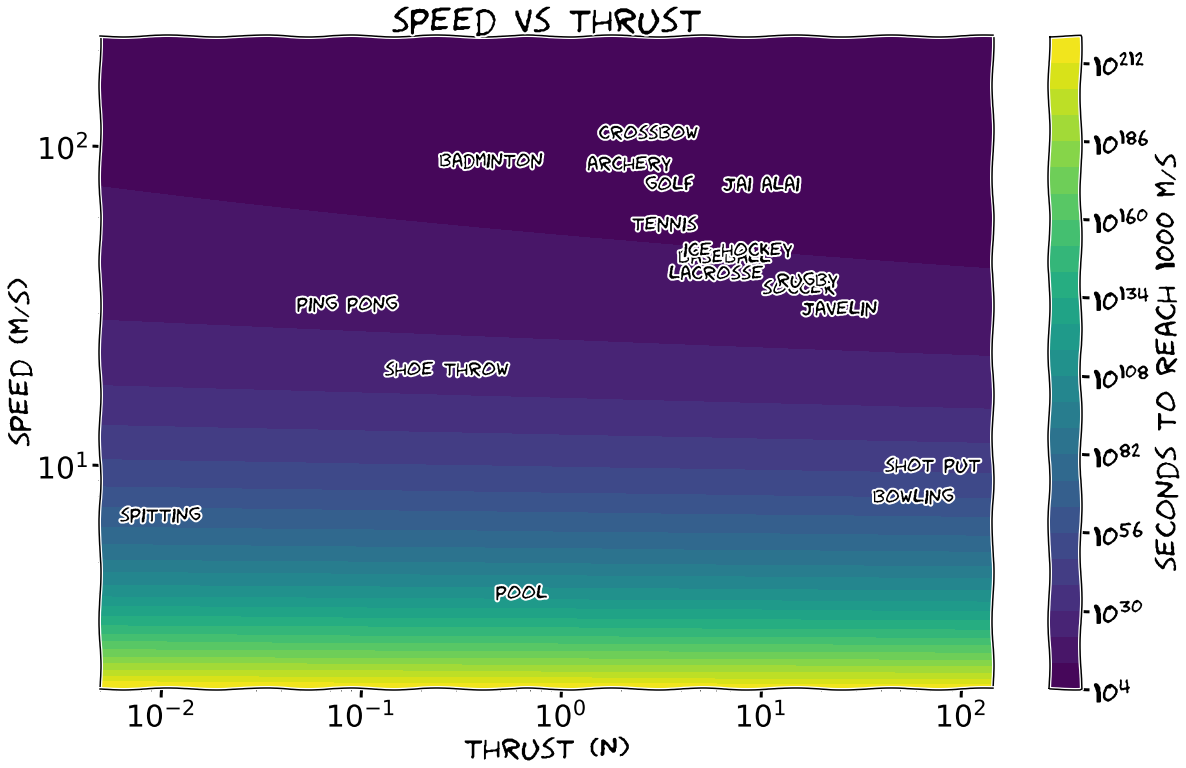

We can use these formulae to figure out roughly what’ll happen in our intersport showdown. For a given sport, \(u\) is just the projectile speed (around 76 m/s for a golf ball and 4 m/s for a pool ball) and the thrust is equal to (projectile speed)\(\times\)(projectile mass)\(\times\)(fire rate). If we assume a constant fire rate of 1 shot/s across all sports for simplicity, we can get the speed and thrust for every sport. Here’s a plot showing the results.

A quick look at this might reveal some oddities. Jai alai (also called Basque pelota) was once an Olympic sport; it’s like wallball but with a giant curved launcher on your throwing arm. Bowling and pool I’ve included even though they’re not Olympic sports. Crossbow shooting I included because our question is ultimately about projectiles launched solely with energy from human muscles, and it’s one of the best examples of that. For the same reason, I didn’t include gun sports. Lastly, running and swimming events don’t have projectiles, so I assumed their respective gold medalists will be throwing shoes and spitting mouthfuls of pool water3.

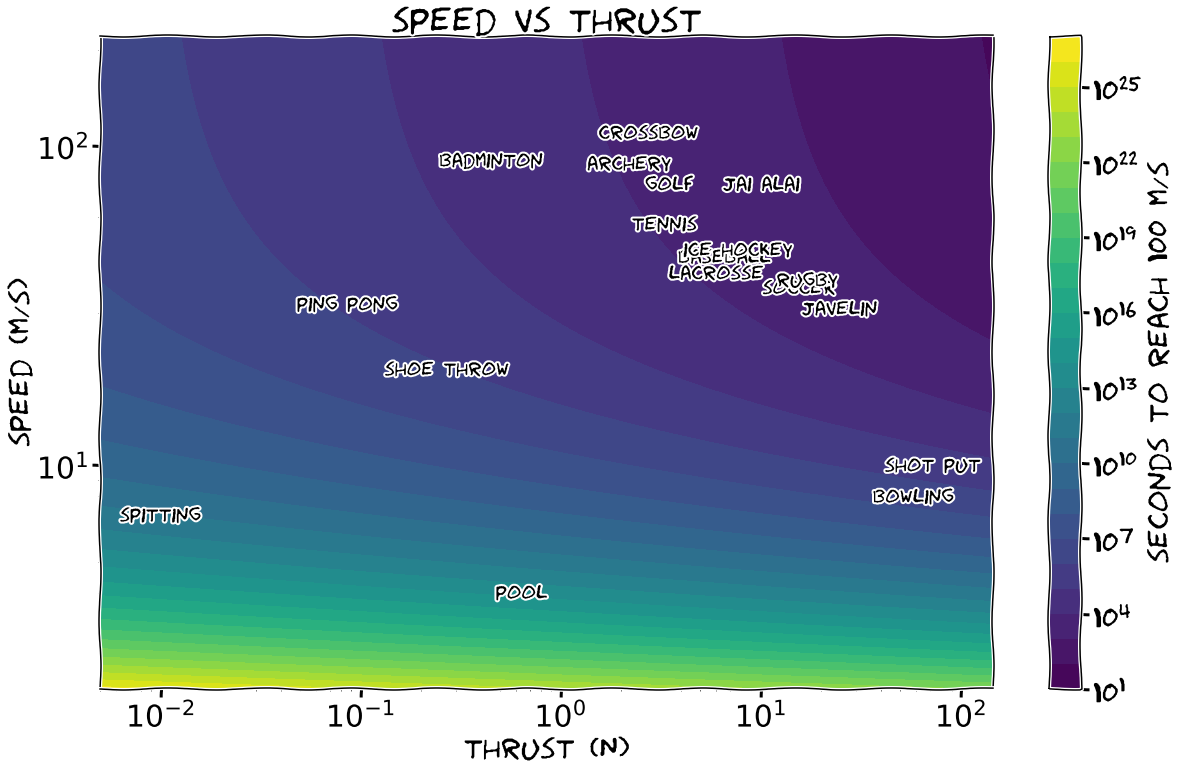

This plot makes it clear that some sports are better than others, but it’s not apparent which is best. To decide, we’ll have to pick a target speed. Let’s say the athlete and their suit are 100 kg, and they’re trying to reach a final speed of 10 m/s. We’ll also assume that the athlete can repeatedly launch projectiles in the same direction without uncontrollably spinning or getting knocked off, but that seems fair; after all, they are professionals. About how long will each sport’s champion take to finish?

This plot shows that the best sport to reach 10 m/s is shot put. It’d actually only take 24 solid throws to finish, which is 24 seconds with our assumption of one shot per second. Most other sports take a few minutes; the swimmers will be spitting into the void for several days.

What if we instead want to reach 100 m/s?

Now the best option is to accelerate with 2053 jai alai throws, which takes a little over half an hour. Due to the exponential in our time formula, however, accelerating with pool balls will now take over a hundred million years. Surprisingly, most high-energy projectile sports are all relatively close, with a time less than a few hours. Actually, at a target speed of 130 m/s, the entire swath from crossbow to javelin is about even! This, I propose, is the ideal choice for Rocketball; the sports without high-energy projectiles can get a handicap.

What if we make the target 1000 m/s?

With this high target speed, the \(e^{v/u}\) term is so dominant that the thrust is basically irrelevant compared to the exhaust speed. The best option now is to use 35 million crossbow bolts, which will take around a year. This is one of the few situations where your best choice is to use a bow in space. All the sports slower than javelin will take longer than the current age of the universe.

This is a decent analysis for the purposes of Rocketball, but these speeds are miniscule on the scale of the Solar system. What if we want to reach 10000 m/s, roughly Earth escape velocity? As you might guess, exhaust speed is even more dominant here, and crossbow bolts are still the best choice. However, you’d need \(10^{43}\) of them. The good news is that they’d hold together under their own gravity, so you wouldn’t need a quiver. The bad news is that the arrow ball would have a bigger diameter than the orbit of Saturn and would immediately collapse into a black hole.

There is, however, a sport we’ve overlooked. The tires of a bike contain air under high pressure, and if there’s a hole or open valve, that pressure will accelerate the escaping air to high velocities. Normal bike valves are narrow and slow down the escaping air a lot, but if you designed a much bigger one (or just punched a hole in the tire) it’d come out much faster - a 50 psi tire would, in the ideal case, accelerate air to 760 m/s! It turns out that you could reach 10000 m/s by ideally releasing enough 50-psi air to fill a sphere with a diameter of 270 m.

How long would that take? By our constraint of only man-powered projectiles, you’d have to pump up the air. This is about 47 billion bike tires’ worth of air, so it’d take around a millenium even if you’re the world’s fastest tire pumper. The release, however, would be quick.

-

and gets to come back to Earth. ↩

-

(this is a lower bound) ↩

-

Spacesuit helmets would admittedly block the spit-out pool water, but since humans can survive zero pressure for short periods and swimmers are already good at not breathing, let’s say they take their helmets off to spit. Another option’s to throw chunks of ice, which would fall between “shoe throw” and “shotput.” ↩