Reflections on introductory neuroscience reading

Have you ever lived in a neighborhood for years and realized, as you prepare to move out, that you never got to know the guy who lives next door? For me, that unknown neighbor is the field of neuroscience. I am nearing the end of a PhD in a lab that does largely neuroscience and live under the umbrella of the Redwood Center for Theoretical Neuroscience, but I confess I’ve never engaged with the field in any serious way.

As with that neighbor you don’t really know, I’ve often seen neuroscience — I regularly pass by it on the sidewalk, so to speak, exchanging cordial pleasantries but never really engaging, always with something just a little more important to do. Look, I’m sure neuroscience is a nice guy and all that, but we just don’t have that much in common! A lot of people seem to like him, but we’ve just never really clicked – and besides, isn’t he the one with all those rats? It’s hard for me to understand what he’s saying or why, so when we pass each other on the street, I usually just smile and nod and continue on my way.

No more. I’ve decided to learn some neuroscience. These past weeks, I’ve been doing basic reading in an effort to absorb some of the big ideas. This post will summarize some of what I’ve learned. If you come from a similar academic background and have a similar curiosity, perhaps you’ll find some of this interesting.

Why would I learn neuroscience?

I’m doing this for two main reasons. The first is self-knowledge: I’m in a reflective period in which I aim to better understand myself, and I suspected that some basic neuro- and cognitive science might help me better understand my own experience — and indeed it has! Seeing the important ways in which our brains are hacky really gives me a sense of humility and a feeling that human experience is often different and much stranger than we conceive it to be, so we ought to really look at it. The second is more general: if you’ve never touched a field, there are often big foundational ideas sitting on the surface for you to learn, and so a fairly short period of learning can give outsize returns because you’re on the steep part of the learning curve. That also turned out to be true — I’d underestimated how much we know about the brain and how easily some of my naïve notions could be improved.

Plan of attack

I’m a physicist by training, and I like to think about general principles and big ideas, so over the past few weeks I read Sterling and Laughlin’s Principles of Neural Design. This is an introductory book focused less on the specifics of anatomy and much more on broad principles which govern neural circuitry across brain regions and across species. This was a good match for the level of detail at which I wanted to learn things — I don’t need to know about, say, the superior temporal gyrus or the difference between norepinephrine and epinephrine, but I do want to know that neural circuitry aggressively tries to minimize wire length and energy consumption. It gives a nice overview of how someone familiar with physical or systems thinking could begin to start thinking about the brain. I also read some of Kandel et al.’s Principles of Neural Science,1 a classic introductory text.

Some learnings

Without further ado, here’s a bunch of stuff I learned.

The brain is very structurally complicated

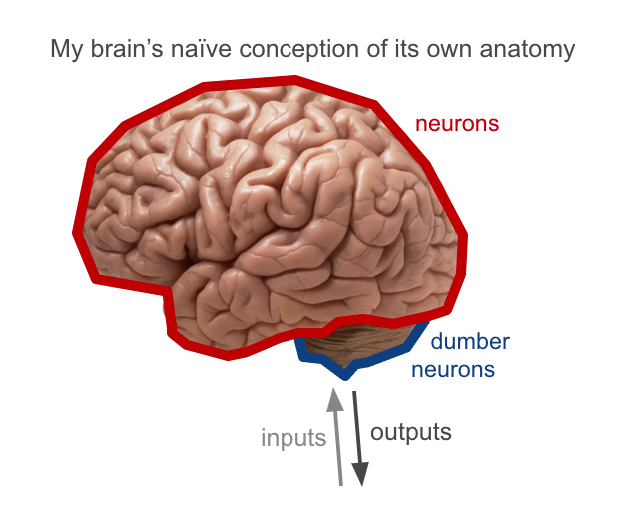

Coming from machine learning, my naive picture of the brain was basically that it’s a big homogeneous mass of neurons initially connected in a mostly random fashion, with inputs to some regions and outputs from others, and that learning from experience leads to gradual strengthening and weakening of neural connections so that this mass of neurons eventually knows and learns.

In reality, the brain is highly structured. This is actually pretty apparent from anatomy, even at a coarse level: the inside of the brain is whitish (containing mostly long insulated communication channels, or white matter), while the outer few millimeters is greyish (containing lots of neurons with dense short-range connections, or grey matter). Different regions of the brain have different textures, with peculiarly-shaped masses on the inside and in the hindbrain.

In fact, even the cerebral cortex — the big wrinkly part that covers most of the outside of the brain — is in reality made up of lots of distinct regions which differ in their cellular structure! Over a century ago, Korbinian Brodmann made close examination of the cytostructure of the cortex and identified some 52 distinct regions with different cellular composition and patterning. Some of these regions have since been found to be robustly responsible for distinct brain functions, like processing sound, processing touch, and language production. The fact that these different regions of the homogenous-looking cortex are physiologically distinct and consistently perform different roles is a surprise to me!2

The homogeneous-looking cortex is actually comprised of many regions of differing functions and cellular properties. Surprisingly to me, these regions do not follow the folds of the cortex!

This complexity extends down to the level of individual neurons. There isn’t just one type of “neuron” — rather, the brain has tens to hundreds of different types of firing and support cells with very different geometries adapted to different roles and parts of the brain. On the small end, cerebellar granule cells are only ~5 µm in size with axons of width on the order of only 200 nm (!). These connect directly with Purkinje cells, which have cell bodies about 10x wider and dendritic arbors that spread out in a striking planar shape as far as several millimeters. The retina, which translates incoming light into neural signals, contains multiple layers of many distinct cell types, starting with specialized rod and cone cells and leading up to the optic nerve, which is essentially a cable-like bundle of about $10^6$ axons which extend for several centimeters (!) from the eye to the visual cortex. The largest neurons in the body stretch from the spinal cord to the ends of the limbs and can be over a meter in length. Thinking of these all as “neurons” seems as reductive as referring to all components of a mechanical system or electronic circuit as just “components” — it’s not wrong, but it’s almost always more useful to work at a finer level of abstraction.

Why are things so complicated?

Here’s another amazing fact which will turn out to be related: in the nematode C. elegans, every individual has exactly 302 neurons, and they’re always in the same place and connected the same way.3 This might seem shocking — after all, aren’t central nervous systems these flexible, adaptive systems that differ between individuals? It certainly surprises me until I remember that, well, the adult human body has exactly 206 bones and some 600 muscles, and they’re always in the same place and connected the same way. Biology is certainly capable of specifying this level of detail. Since the nematode doesn’t really need to learn, why not just hard-code a rigid rule-based control system for its simple body?

The important fact here is that the main role of a central nervous system is not to learn, it is to dictate global actions and share information between different parts of an organism’s body necessary for doing so. Sterling and Laughlin illustrate this beautifully by pointing to the rudimentary chemical and electrical signaling of the paramecium — which is hard-coded and includes commands like “back up” and “turn” — as the ancestor of our own nervous systems. Learning in its various forms is sort of a remarkable recent development which allows a nervous system to adapt to its environment. In this light, it makes a lot of sense that the brain would be so complicated — it’s evolved from nervous systems like those of C. elegans, except instead of 302 hard-coded neurons, our brains have a few hundred hard-coded parts, and the fact that some learning can occur within each part is somewhat secondary to the overall control flow.

The brain generally obeys a handful of low-level design principles

What does it mean to “understand the brain”? Coming from machine learning theory, I’d held this notion to a high bar: surely understanding in neuroscience would mean we know the precise encoding scheme for memories, or can give a mathematical model of human reasoning played out in neural firings, or concretely explain what happens neurologically when you imagine something. I hadn’t appreciated the degree to which these cognitive, experiential things are really just one level of the layer cake of neuroscience. There are in fact many other levels of abstraction which we understand fairly well!

Principles of Neural Design sets out to collect some low-level principles, and I found many of these quite compelling! Here are a few:

- Compute with chemistry whenever possible. Neural firing is energetically expensive — it’s much cheaper to transmit signals via releasing chemicals which travel diffusively! However, diffusive signaling spreads only as [distance] ~ [time]${}^{1/2}$, which ends up meaning it’s usually not a good choice when you need to go, say, more than a millimeter in one direction. Chemical computing tends also to require fewer parts and take up less space. The animal nervous system reliably uses chemical signal for either short-distance processing (e.g., across synapses or within cells) or slow global signal transmission (e.g., hormones in the bloodstream), and makes surprising use of proteins which change conformation in the presence of a ligand in order to perform basic computational operations.

- Send only what is needed. Signal transmission is expensive — the brain uses almost 20% of the body’s energy, over half of which goes to neurons’ ion pumps! It’s therefore important to be economical in what’s sent — sending half as much information roughly cuts the energy cost in half. Across areas, the brain has robustly developed to only transmit necessary information and compress it as much as possible — often in ways that seem surprising given our experience of the world! The classic example of this is the visual system — we only have detailed vision in the central region of our field of view, and it’s shockingly low-res in the periphery — people regularly underestimate how bad their peripheral vision is. I honestly find it a bit annoying when I notice it, but it makes a lot of sense evolutionarily — the point of the visual system isn’t to provide our brain with a beautiful detailed image of the outside world, it’s to give us enough information to do survival and social tasks, and we can do these tasks quite well with only a small area of high-res vision that we scan around! This principle also applies to the postprocessing that occurs in the retina, which famously compresses visual information by translating to a sparse basis before transmission through the optic nerve.

- Send at the lowest acceptable rate. A cool fact I hadn’t known: sending a neural signal faster requires a thicker axon, which for biophysical reasons turns out to require superlinearly more resources and energy! The brain’s thus incentivized to send information as slowly as possible. This is basically true everywhere in the brain — I suppose it’s evolutionarily “easy” to tweak axons to be thinner and slower, so they’ll always tend to settle down to the slowest rate that works well enough. An amazing example of this is the speeds of different sensory modalities: olfaction (smell) has no need to be fast, so it uses a cable of $10^7$ very thin axons to send information quite slowly, while on the other end, the vestibular sense (balance) needs to send little information but needs to send it fast to keep us upright, so it uses far fewer axons which are about 100x cross-sectionally larger.

There are, of course, plenty of exceptions here: the design of the vertebrate retina is famously silly, with processing circuitry partially blocking the photosensitive cells and the optic nerve creating a blind spot in each eye. I’m not sure how to square these cases with the observation that the brain often does a good job finding efficient design. Maybe the satisfaction of these principles is achieved via a kind of local gradient descent – e.g., by making small adjustments to axon thickness, neuron count, connectivity, and so on – and these weird cases reflect evolutionary “local minima” that are hard to escape?

- Minimize wire. Rather intuitively, longer axons take up more space, cost more energy, and slow signal transmission, so the brain tends to shorten wires as much as possible. This is achieved partially at the level of individual neurons, which tend to take shapes and choose branching points that reach all their connections in a local minimum of total distance.4 It is also achieved via organization of neural regions into maps — for example, the early visual cortex is arranged spatially in a 2D way that mimics the retina, which minimizes diagonal cross-wiring. Some brain areas have peculiar neural organization, like the aforementioned fan-shaped Purkinje cells stacked in the cerebellum, and this organization allows for lots of dense connections in a small volume.

- Complicate and specialize. The cost of a neural design is not in its complexity, it’s in the amount of resources it uses — that is, space, energy, time, and physical materials. If a neural circuit can be complicated in exchange for using less of one of these, it often will! As a result, there are a huge number of different neurons with different geometries, firing rates, sensitivities, and so on, which economize some resource. Every part of a signaling pathway in the brain is thus adapted to its place in the chain, and will adapt so it fulfills its role — transmitting with a particular fidelity, across a particular distance, and in a particular time — as cheaply as possible. An example I like: opsin molecules in rod cells in the eye are occasionally activated by random thermal noise… but they’re designed to be just robust enough that this noise level is just a few times below the activity rate when looking around in starlight.

There are many levels at which we might want to “understand” the brain

As aforementioned, I hail from physics, where the bar for understanding is quite high: one expects a tight, testable, ideally-mathematical theory before one believes one understands a complex system. Applied to the brain, a physicist might want, say, a clean, elegant, mathematical theory for how high-level concepts are represented and manipulated in the brain before saying we understand what it’s doing, perhaps using notions of sparsity, information theory, high-dimensional geometry, and so on. This still seems like a reasonable-albeit-distant dream to me,5 but there are many more levels at which we could understand the brain. Here are two:

Low-level component design. As discussed in the previous section, we can very much ask questions like: “given that this component performs this signaling task, why is it designed like this?” Questions like this are among the most answerable in neuroscience — appealing to efficiency principles seems to work pretty often! Of course, we often don’t know what task a component performs.

Broad stories about high-level information processing. I hadn’t appreciated the degree to which you don’t need a mathematical description of learning in order to find pretty compelling stories about what different parts of the brain are doing. For example, we can tell loose stories like “when engaged in conversation, the auditory cortex preprocesses incoming sound, Wernicke’s area processes the sound as speech, and Broca’s area is responsible for speech production.” From the perspective of a physicist, this is an incredibly vague story: what do you mean by “processing the sound as speech”? What is involved in speech production? And how on earth is this all encoded in a bunch of noisy neurons? These are very real questions, but the important realization for me is, well, you don’t need to know that for a lot of stuff. For example, if a patient’s Broca’s area is lesioned, they’ll be unable to produce speech correctly. If a patient’s Wernicke’s area is lesioned, they’ll be unable to understand speech but, remarkably, able to produce it. These areas light up under brain scanning when performing relevant tasks. This incredibly vague story seems to work, actually — well enough to inform medical interventions! We didn’t actually need to know how the neural circuits work: vague, high-level stories are useful enough for some real understanding.

It seems to me like most of our high-level brain knowledge is of this form: we have stories like “Part A is responsible for task X. Task X also requires input from Part B, so Parts A and B are wired together, and that wiring strengthens as one performs more of Task X.” We pretty rarely have a low-level understanding of how neural circuitry is computing, but we have stories like this for lots and lots of parts and tasks. This view is reminscent of Marr’s three levels of abstraction, which proposes that computing systems can be studied at the level of the task ultimately performed (the highest level), the algorithm used to perform that task (the middle level), or the hardware used to implement that algorithm (the lowest level). Perhaps a good story here is that neuroscience has made major progress on the lowest and highest levels, but it’s still unclear how to connect them: we cannot extract the algorithms performed by neural hardware which implement the high-level functions which we know brain regions to perform.

One interesting takeaway I glean from all this is that it now seems like the thing I purport to want — a simple mathematical description of learning — actually lies not at the highest level of abstraction but at an intermediate level, above the level of small circuits but below the level of brain regions. I’m also less confident that it’s really a good goal!

How do we learn?

The nature of learning is still pretty unclear to me from my reading. It seems like there are a bunch of different mechanisms — synapses that have fired recently more readily fire again in the following seconds and minutes, synapses that have fired many times tend to increase their sensitivity, dopamine release (which is globally mediated) tends to reinforce neurons to do whatever they were just doing. I’m confused as to how to think about these mechanisms — is there a sharp difference between short-term and lon-term memory? Is there a difference between short-term memory and “what you’re thinking about right now”? Is most learning distributed and reward-signal-free, or is it top-down modulated as in machine learning? What tasks even count as “learning” — I could believe there are many more than the typical testing suite I envision! I feel I’ve gotten a bit of flavor for some of these learning mechanisms, but not enough to have any real picture of learning in the brain.

This set of questions seems particularly interesting where it intersects with our everyday human experience. For example:

-

What’s going on neurologically when we forget things?

-

When you hear or use an usual word, you’re more likely to notice or use it again soon after. Is this explicable through some known neuro learning mechanism?

-

What’s the difference between factual learning and wisdom? Why does some learning feel like it affects our worldview, while other learning feels like just memorizing facts?

Fun facts

Some disconnected fun facts from my reading:

-

The brain has a region called the suprachiasmatic nucleus which takes in input from the retina regarding how generally light a scene is and serves as the body’s 24-hour clock.

-

Neurons in the brain are outnumbered by glial cells (i.e. everything else) by a factor between 10 and 50.

-

The skull is physically full of brain, and synapses expand when they get stronger, so it’s often the case that practicing one skill causes part of the brain to physically grow, which causes other parts to shrink! This can have expected-but-still-alarming consequences in which learning one skill directly degrades performance at another — for example, learning to read decreases one’s ability to recognize faces! (I’m confused as to what to take away from this in light of the common claim that the brain’s storage capacity is so large it’s virtually unlimited.)

Closing thoughts

I set out to see if I could glean a high-level view of the field of neuroscience from some foundational background reading. I actually feel I’ve managed to do that to a modest degree! It was an endeavor well worth the time investment; I’d recommend it to others who are interested, and will probably do it again myself with different fields.

In general, I’d say we actually understand more about neuroscience than I’d thought! While the things I thought were mysteries generally do seem to be unknown, I was blind to the many levels at which modern neuroscience examines the brain and thus to the very real progress we’ve made towards characterizing the brain’s functioning and relating it to both evolutionary pressures and our own human experience. I’m left quite impressed by the sheer amount of work required to get to this point — as an acquaintance recently told me, it takes a PhD’s worth of work to get one line in a textbook.6

The most profound conceptual discoveries in the sciences — perhaps simply in general — often build bridges between two things that previously seemed to live in different worlds. My interest in neuroscience basically stems from a hope of this nature. Our lives as human beings take place largely in the world of our own internal processing: our cognition, sensation, and action; our feelings, reactions, and dreams. However, we have far more concrete, reliable understanding of the physical world of atoms and molecules, proteins and neurons, circuits and brains. I’m excited (both selfishly and altruistically) by the prospects for building bridges between these realms, starting to understand our own human experience in terms of basic science.

Thanks to Chandan Singh and Mike DeWeese for feedback on this post!

-

Yes, these two books have confusingly similar names. ↩

-

It took a protracted debate to arrive at the modern view of the cortex as composed of distinct regions which perform different elementary processing operations. Interestingly, this idea originated with phrenology, which in the early 1800s posited that the brain is comprised of some 30+ regions responsible for personality traits like “wit,” “religiosity,” “benevolence,” and so on. This framework is now understood to be totally wrong and based in little to no evidence, but the idea of a few dozen distinct brain regions was right - by accident as far as I can tell! After that came an era dominated by the “aggregate field view” that essentially held that the whole brain does everything, after which the modern “cellular connectionist” view took hold. Most of the early evidence for the modern view came from studying patients with certain cognitive or motor impairments and consistently finding damage in the same part of their brains. ↩

-

Fun fact: C. elegans neurons also use analog signaling, not pulsatile signaling (aka “firing”). ↩

-

Tree branches and root systems do something like this too! ↩

-

In all honesty, I personally find this question so appealing and seductive that it’s distracting from more concrete problems. ↩

-

That said, it’s likely I’m too optimistic about understanding here given that I’ve just read a compendium of lots of things we understand. It seems likely that there are lots of things we don’t understand, even at the lowest and highest levels of abstraction: plenty of microscopic neural processes remain difficult or impossible to characterize with current tools, and there are surely lots of macroscopic brain areas about which we don’t have really compelling stories as to their function. ↩