The gravitree

I am now in the 3rd year of my physics PhD, a path motivated, more or less, by a strong desire to figure out the basic rules of the universe. There are many reasons we should try to understand nature: in addition to simple curiosity, it’s my sincere hope that the small light I shine into the unknown might help discover things that one day make the world a better place. That, surely, will be the noblest use of the scientific knowledge to which I find myself a fortunate heir. In the meantime, though, I really like to use it to make weird stuff.

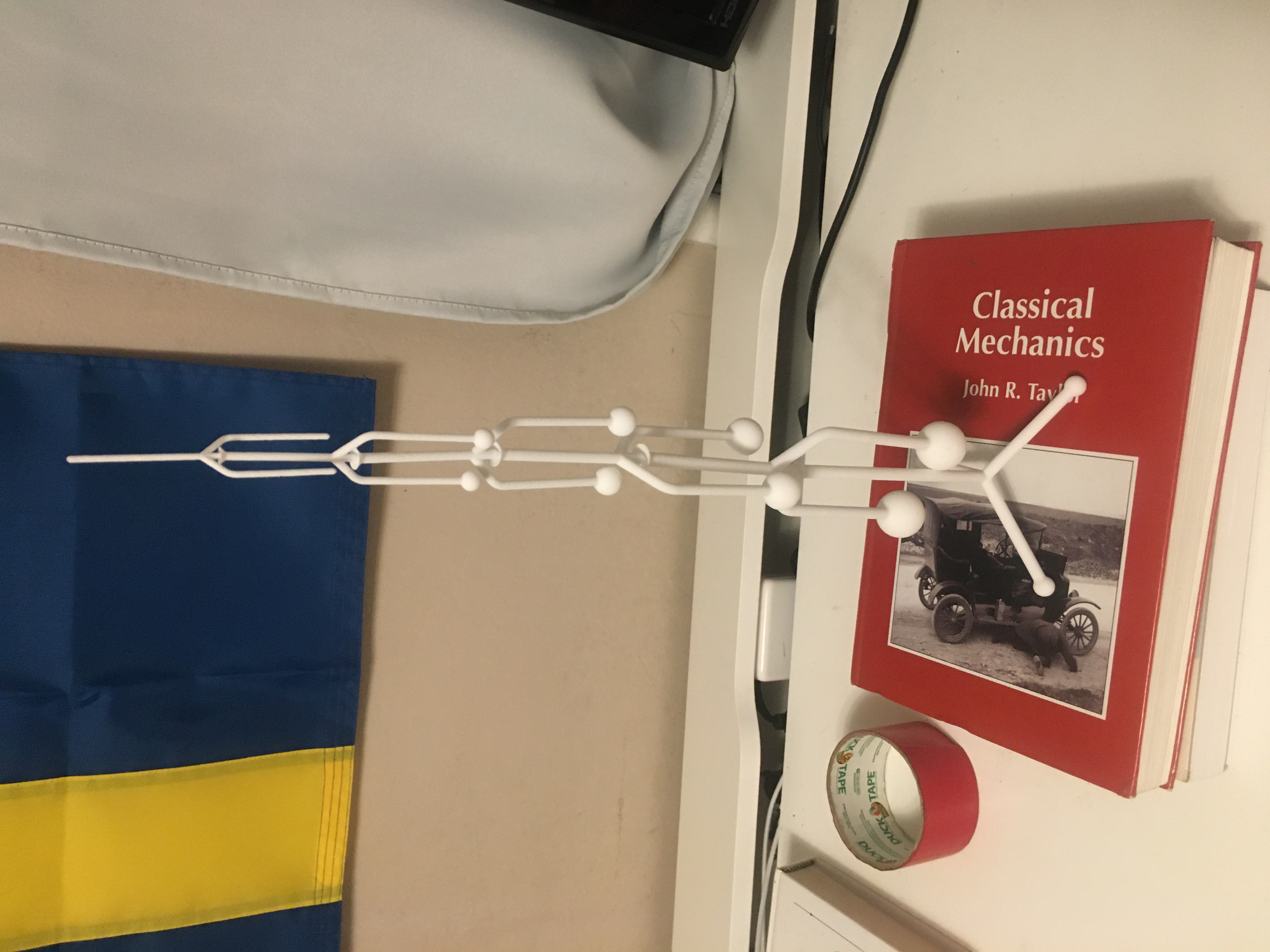

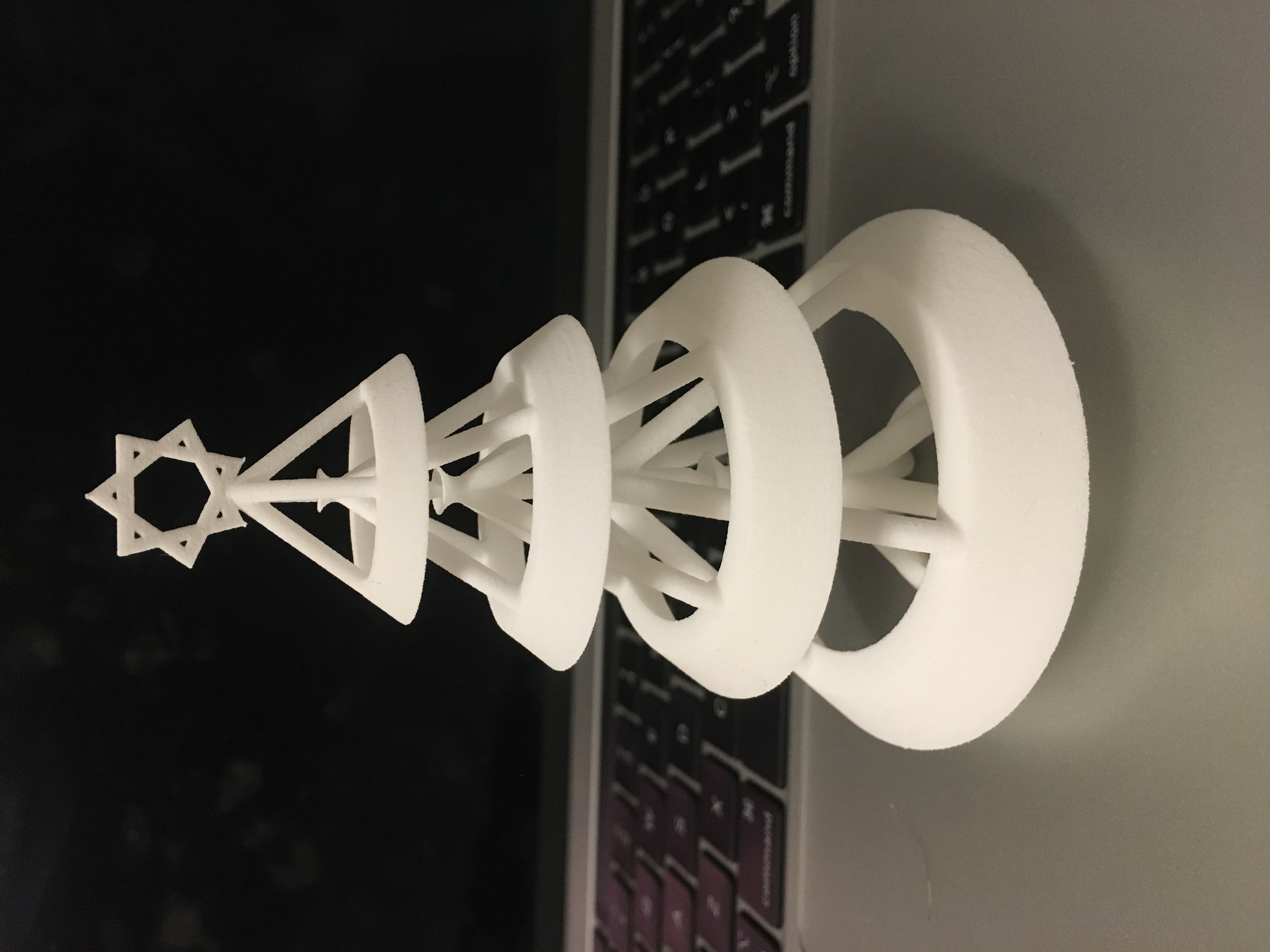

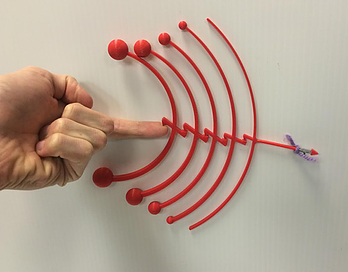

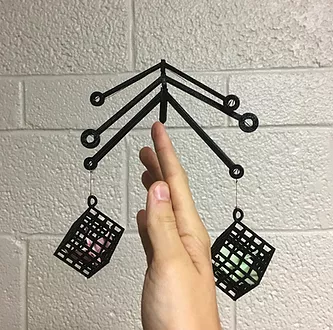

I’m writing this to introduce and explain the gravitree, a type of balancing kinetic sculpture that I’ve been 3D-printing for years. It requires only high school physics to understand (and that was all I knew when I came up with it), but its hypnotic and counterintuitive motion is unlike anything else I’ve seen. It consists of a number of freely-moving pieces, arranged one atop another in a stack, with just the bottommost piece supported. Here’s what it looks like.

The stack is easy to assemble and absurdly stable; when people first hold it, they’re usually surprised by how easily it stays upright and the way it stays balanced even during drastic motions. I currently have several of them up as room decorations and desk ornaments, and I’m pretty sure they’ll stand through a sizable earthquake. What’s the trick?

It turns out the gravitree is best understood from the top down: we’ll first take a close look at the top piece, then at the top two together, then the top three, all the way down. As we’ll see, it’s just using the same trick again and again.

The key to understanding the sculpture is the concept of center of mass. Think for a moment about how gravity acts on your body. It pulls down on every gram of you, all throughout your volume. The total force is equal to your weight, but the way that force is spread out in space depends on your shape and your pose.

An object, like you, can have quite a complex shape, so you’d naturally think it would be very complicated to figure out how gravity will pull and spin a particular object. It turns out, however, that as long as the object doesn’t bend much, we can pretend that all the force is pulling at one point, called the object’s center of mass, and we’ll correctly predict its motion. As the name suggests, the center of mass is the average location of mass in the object, and it’s closer to bigger, denser parts.

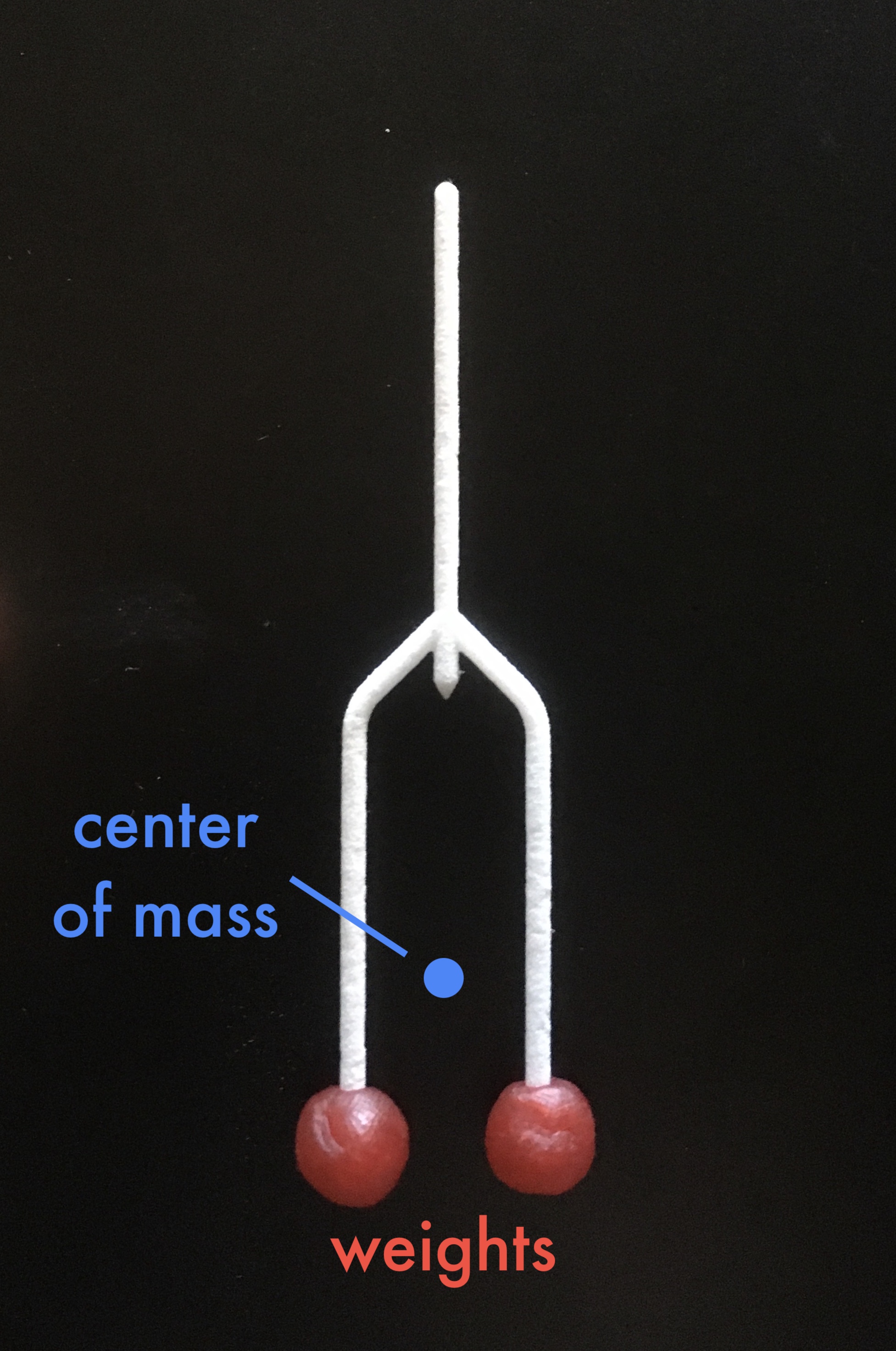

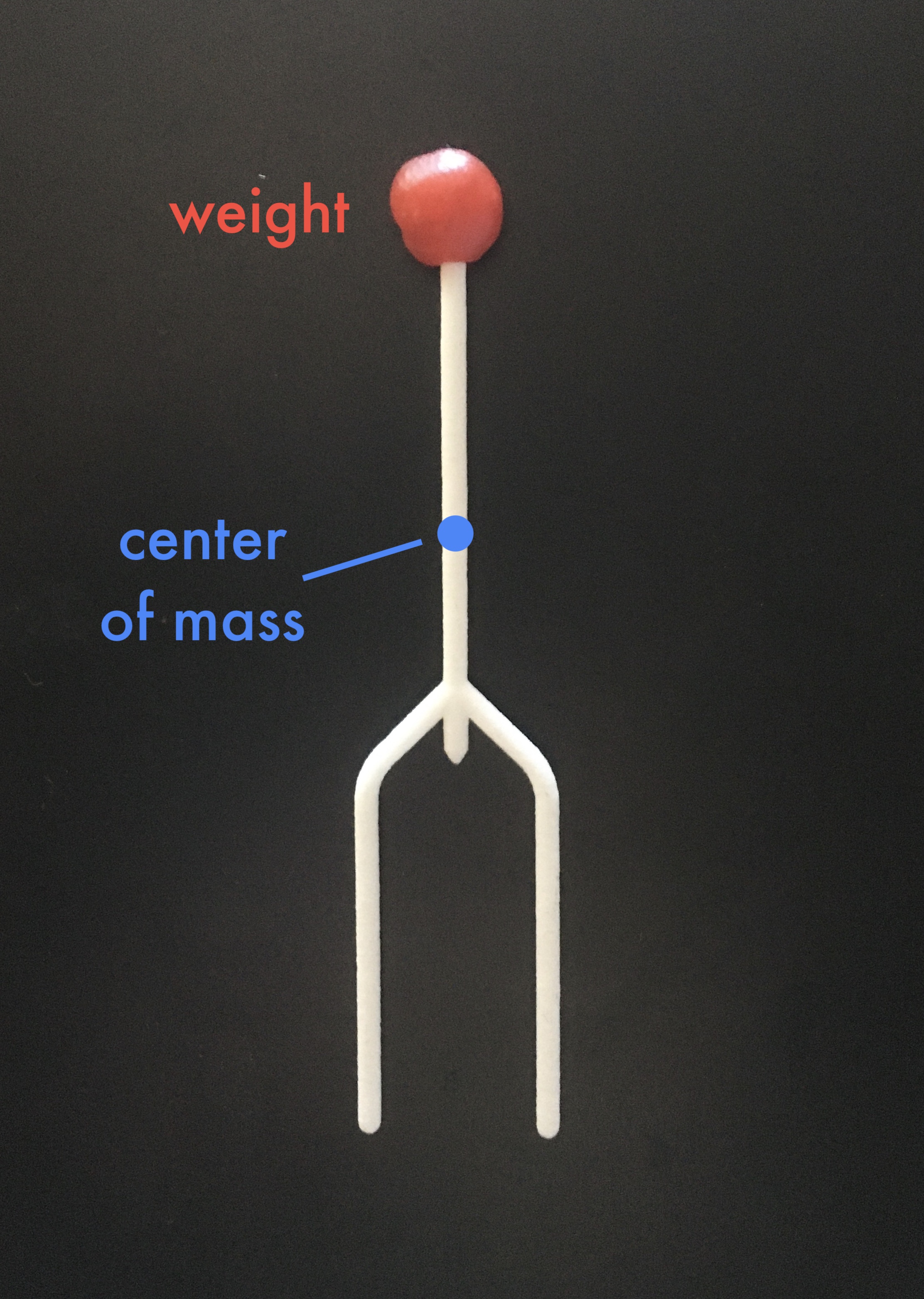

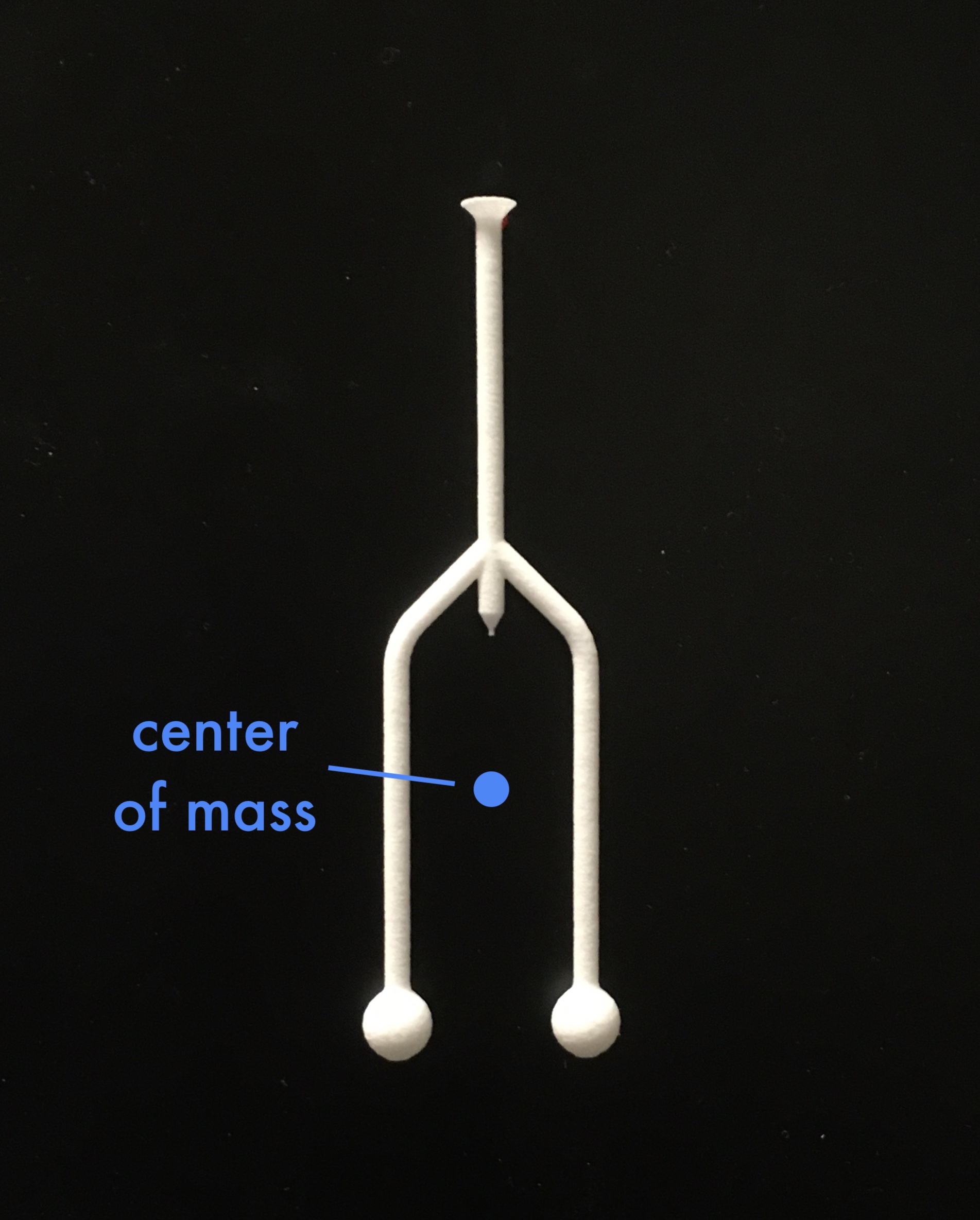

Let’s look at the center of mass of the top piece of the gravitree. First, I’ll attach two weights to the bottom, which will bring the center of mass to well below the balance point. This makes the object a lot like a pendulum, which just consists of a point of rotation and a big mass some distance below it. Like a pendulum, it’s very stable - gravity tends to try to pull it back to vertical - and when we poke it, we see it follow quick oscillations.

By contrast, if I put the weight at the top, the center of mass is now above the balance point, and it’s unstable: gravity now tends to pull it away from vertical. If the previous weighting’s like a pendulum, this one’s like a pencil balanced on your finger. It won’t stand on its own.

For a balanced object, these are the choices. It can either be stable or unstable, switching from one to the other as the center of mass crosses the pivot point. This raises an natural question, though: what happens if you start with a stable object and push the center of mass closer and closer to the pivot but never crossing it? How would such a barely stable object move?

That’s the secret of the gravitree. This piece is just barely stable, and because of that, it swings like a pendulum, but very slowly. The technical reason’s that, since the center of mass is so close to the pivot, the torque from gravity is so small it gives the object only a tiny angular acceleration relative to its moment of inertia.

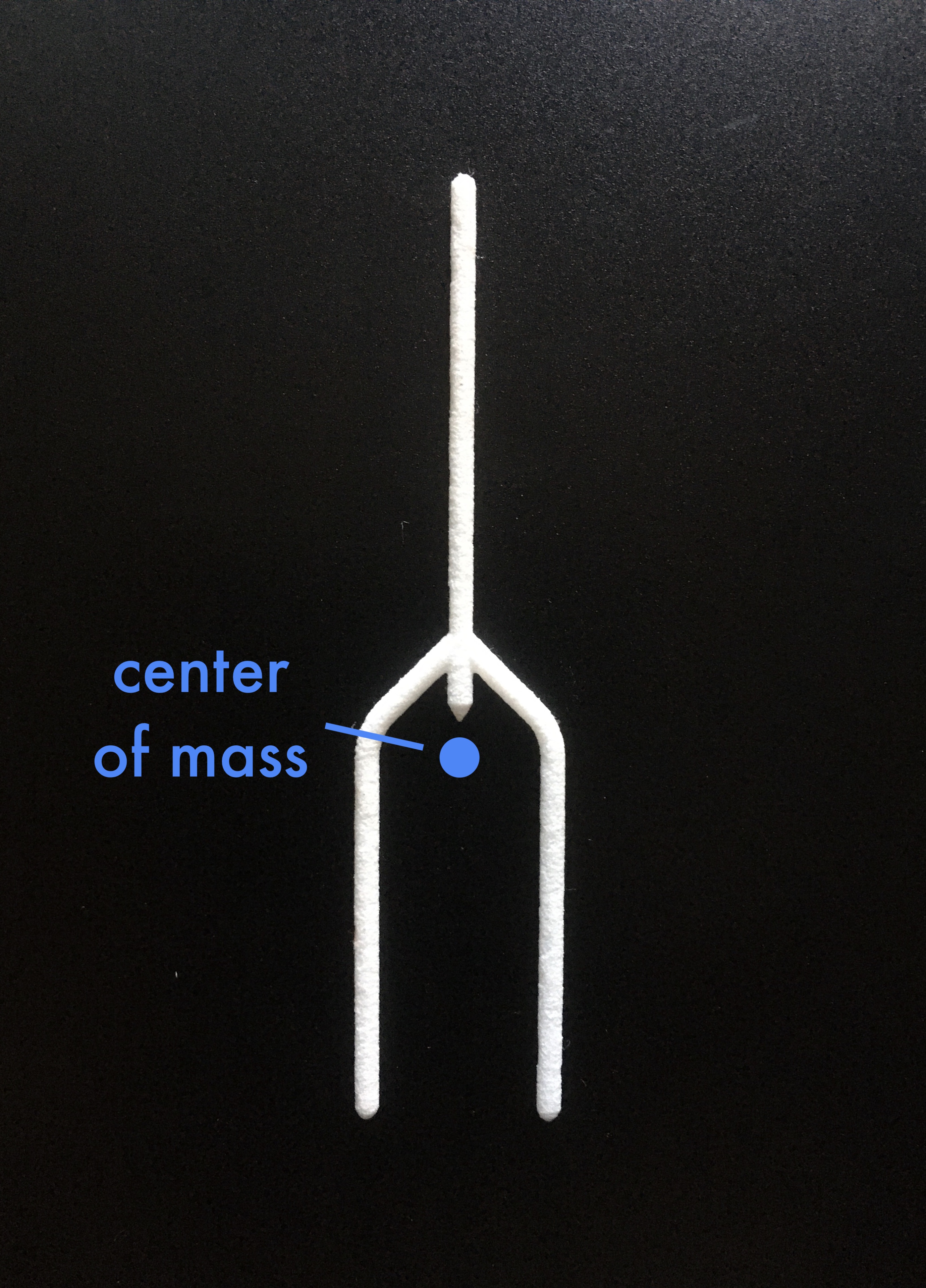

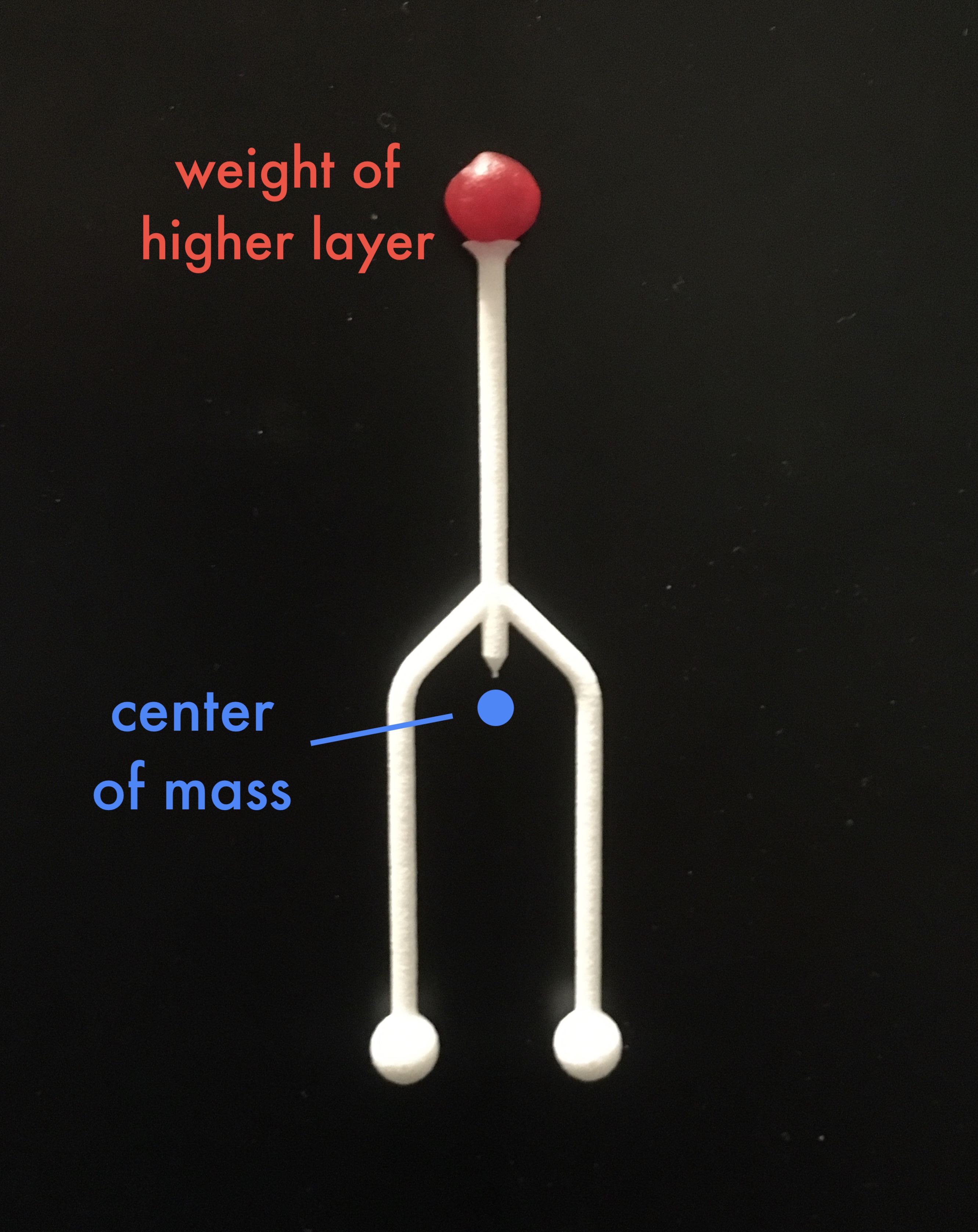

This explains both why the top piece is stable and why it moves so eerily, seeming to move through space without swinging around like you’d expect it to. What about all the other pieces, though? It turns out they all use the same trick, but when balancing a lower piece, you have to imagine the weight of all the higher layers acting on its top. To illustrate that point, let’s look at the second-highest piece. Without that extra weight, it’s very stable, but with that weight, it’s barely stable like the topmost piece.

We can use this trick again and again all the way down. When I designed this sculpture, I used Autodesk Inventor’s center-of-mass-finding feature to balance the pieces from the top down, adjusting the sphere sizes to make each new piece barely stable under the weight of those above it. The end result is an entire tower that’s paradoxically both barely stable and yet very hard to accidentally knock over. This basic idea can take many different forms - here are several other gravitrees I’ve made over the years.

There’s a deeper trick we’re playing here, one that I see in inventions from reaction wheels to faster-than-wind sailboats: once we know the precise rules of the universe, we can saunter just up to the edge of impossibility and thumb our noses at Nature like a toddler who knows they’re not technically breaking their mother’s rules. For all of science’s immense capacity for social good, that sort of thing - the feeling of doing what seemed impossible until you stopped to think about it - is a key part of what compels me to study physics, and I think it’s a potent way to inspire the curious to think a little closer about how the universe really works.